There is a lack of environmental justice in the UK. People living in the poorest neighbourhoods tend to be worst hit by environmental damage – for example, pollution. 82% of the cancer-causing chemicals emitted from large factories in England are from factories in the most deprived wards. And people in poorest areas don’t get a fair share of environmental benefits either, such as access to parks and open spaces.

Fuel poverty is high and rising, and the Big Six energy company pricing systems penalise people who can’t afford to use much electricity or gas – tariffs are high for low levels of consumption, and lower for higher levels of energy use.

This is clearly nuts – except from the energy companies’ point of view, because it rewards people for buying more gas & electricity.

Flood risk and flood impacts can also be seen as environmental justice issues. There are relationships between patterns of social inequality in the UK and people’s exposure to flood risks. And the impact of flooding is related to patterns of social inequality too, as people on low incomes suffer additional problems because they’re short of money to insure against and deal with flood damage.

People can assert their right to environmental justice with regard to flood risks, flood impacts or any other environmental issues. To tackle social inequalities and claim our right to take part in decision making about flood alleviation and other policies that will reduce flood risks in their area and reduce the impact of flooding on them.

Climate justice

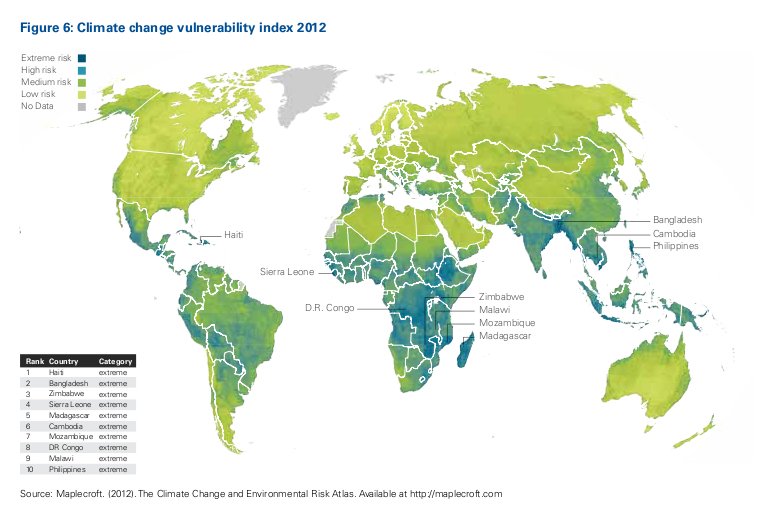

Climate change is strongly associated with environmental injustice. The global oil & gas companies, and the governments and international organisations whose policymaking they have effectively captured, expect people and countries who have barely contributed to climate change to bear the brunt of its consequences. Internationally, the countries that are most at risk from climate change are in the global south. With hardly any fossil-fuel based industries and energy, they haven’t created the carbon emissions that are causing climate change. They are facing the consequences of actions in industrialised countries.

Climate injustice in the UK – low income households produce low carbon emissions but are paying most for low carbon policies

Climate change policies within the UK likewise take little account of environmental justice.

Research from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s (JRF) Climate change and social justice programme shows that carbon emissions are directly related to income – ie higher income households emit far more carbon emissions than lower income households. Asking both high and low income households to reduce emissions by the same amount is quite inequitable.

Another JRF report points out that in the UK:

“The poorest fifth of the population have already exceeded the Government’s carbon reduction target for 2020. Their direct household carbon emissions – for home energy, transport and air travel – are already 43% below the GB average.”

Lower income households have much lower carbon emissions than others, but they are paying more than their share of the costs of low carbon policies and are due to receive less than their share of the policy benefits.

Various presentations at the 2006 Inequality and Sustainable Consumption Seminar at University of East Anglia made the point that social fairness requires low income/poor households to have more access to transport, housing and other socially necessary products and services that produce or embed carbon emissions – not less.

Various presentations at the 2006 Inequality and Sustainable Consumption Seminar at University of East Anglia made the point that social fairness requires low income/poor households to have more access to transport, housing and other socially necessary products and services that produce or embed carbon emissions – not less.

“Social justice and low carbon communities” by Sara Fuller and Harriet Bulkeley, Durham University, May 2012 reviews the justice aspects of current policies/programmes aimed at supporting low carbon communities in the UK. It says that it’s unclear how community-based approaches to making a socially just transition to a low carbon society can achieve this goal. To make a socially-just transition requires attention to climate justice at a local scale.

The Aarhus Convention is supposed to protect the public’s right to environmental justice.

Correction

Also there is no duty or VAT levied on aviation fuel. Most low earners won’t be able to afford foreign travel whilst the top earners make a few plus business flights. One return transatlantic flight is around 1 ton of CO2.