The government and many environmental groups encourage the public to switch to products with low carbon footprints and to use less fossil-fuel energy. But Tim Jackson, part of the University of Surrey Research group on Lifestyles, Values and the Environment (RESOLVE), has concluded that (p15):

”banking on a market revolution driven by green consumers is a forlorn hope”.

This is mainly because, as individuals, we have a limited set of options.

We also simply don’t know enough to make the right buying decisions. Unintended consequences can mean that trying to buy our way out of climate change through green or ethical consumerism actually ends up making matters worse, as with the move to replace diesel with palm oil.

Heather Rogers, author of Green Gone Wrong, explains how we’d be more effective taking political action than buying “green” products.

Brian Milani points out that the problem isn’t so much the mass consumption economy, as inequality. This drives the obsession with economic growth, as a way to avoid redistributing wealth, by the promise of floating everyone’s boat a little higher. Milani suggests that to ignore this and to fetishise overconsumption as the main cause of environmental damage

“amounts to blaming the victim.”

So why do a fair few people buy the myth that green consumerism and behaviour change are going to solve the environmental and climate problems that we face?

Ethical consumption as a status marker

Many people buy and use green/ethical products as a way of identifying or marking their status, for instance when green consumers badmouth people who don’t share their purchasing habits.

Green/ethical products usually cost more than other products, so this creates a kind of ‘brand community’ of people with money.

And brand communities based on taste are inevitably self-limiting. If everyone displays the same taste by buying the ‘brand’, it can no longer serve as a mark of distinction (or status marker). So this pretty much closes off ethical consumption from the mass market.

Our everyday lives are structured by the way society’s organised, what materials and skills we have and how our social status is tied up with the stuff we have and use. That’s not to say that these things can’t change – they do. But most likely not as the result of individual consumer choices.

Research has found that people with “green” values behaved in the same ways and had the same carbon footprints as people who didn’t share those values. So there’s a gap between people’s values and intentions and what they can actually do.

Nudge nudge

Despite this, national and local governments are very keen on trying to change people’s behaviour so that we reduce “our” carbon emissions.

You might not realise it – and the government would prefer that you didn’t – but you’re almost certainly the target for government behaviour change initiatives that aim to ‘nudge’ us into making better decisions. Apparently we don’t make very good ones, left to our own devices. Why else would the UK be facing problems like stubbornly high carbon emissions, human-influenced climate change, epidemics of obesity, diabetes, depression and other mental illnesses, family breakdown, high unemployment, binge drinking and massive food waste?

It can’t be anything to do with a neoliberal political system that lets companies run riot, without effective regulation. It’s all our fault – we must mend our ways.

That’s the theory. But recent studies, including the House of Lords Science and Technology Committee’s Behaviour Change Report, suggest that behaviour change policies generally seem to be about as effective as King Canute telling the rising tide to stop – and they may not be ethical either. This is because behaviour change interventions aim to bypass people’s awareness and induce them to act in ways they haven’t thought about.

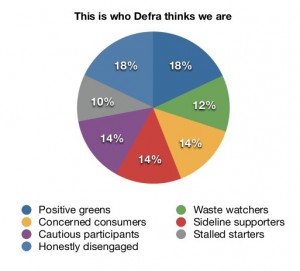

The Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) proposed behaviour change programmes which combined “top down mass engagement” with “some targeting of segments (or groups within these segments)”.

The Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) wants to target specific behaviour change interventions at different sections of the population, according to whether or not they see themselves as green. This is likely to be extra-pointless. A recent survey shows that – with green values or without – people’s energy consumption and carbon emissions are the same.

The Behavioural Insights Team wants to make us better consumers

Despite this evidence, behaviour change is central to current UK government policies. The Coalition Agreement announced their intention of

“finding intelligent ways to encourage, support and enable people to make better choices for themselves”,

preferring this to policies that involve regulation or public spending – which it called “bureaucratic levers”.

The Coalition set up the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) to oversee behaviour change policies. Accordingly, government is forming partnerships with businesses and local authorities, to use ‘behavioural insights’ to encourage people to buy products that will make their homes more energy efficient.

This is the basis of the Green Deal. It assumed that people will take on debts to pay for improvements to the energy efficiency of their home, in order to save money by using less energy. The plan is that the money saved on energy bills will repay the debt.

The Green Deal has replaced publicly funded Local Authority home energy efficiency retrofit schemes, which had their funding cut by the Coalition government’s Comprehensive Spending Review.

But later down the line (September 2014) the House of Commons Select Committee has found that the Green Deal isn’t working.

The problem is market failure, the solution is better consumers

Behaviour change policies are rooted in the belief that everything boils down to the so-called free market – remember Maggie Thatcher’s “There is no alternative” and “There’s no such thing as society”?

According to this story, social or environmental problems like obesity, food waste or high carbon emissions happen because the market – for food, or energy – isn’t working properly.

A Report by the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) identifies that household carbon emissions are caused by these market failures:

- households’ failure to take account of how their consumption decisions damage the environment

- households’ lack of access to information about the fact that they can save money through buying energy efficient products

- households’ failure to act on this kind of information, when they are aware of it

This conveniently lets government off the hook of having to regulate fossil fuel companies. It equally lets them off the hook of having to raise taxes to spend public money on concrete measures like investing in decent public transport or decarbonising the national grid. It reinforces the view that people are primarily consumers – not citizens who make political demands for collective action to improve things.

Selling brotherhood like soap, and shaping your unconscious impulses

Behaviour change policies originated in the practice of so-called social marketing, which first came to attention in a 1950s psychologist’s paper called Merchandising Commodities and Citizenship on Television.

It asked,

“Can brotherhood be sold like soap?”

and answered “Yes”.

By the 1970s, social marketing was taking off. The New Labour government embraced social marketing in its climate change reduction policy, focussing particularly on changing people’s behaviour in order to reduce their household and personal transport carbon emissions.

Nudges aim to change what’s called the “choice architecture” – in other words, the elements that shape people’s unconscious impulses to buy. ‘Nudge’ techniques include:

- choice editing – removing choice from the buyer, eg by phasing out fridges that are lower than a C rating on the A-G energy efficiency scale, or, more recently, phasing out the sale of incandescent light bulbs

- changing the physical environment, eg reducing road capacity, increasing traffic calming measures and pedestrianising town and city centre, in an attempt to reduce people’s use of their cars

- changes to the default position – eg the proposal that people should have to opt out of organ donation, rather than opting in

- using the power of social norms – eg using people’s social networks to get more people to buy energy efficiency products, like loft and cavity wall insulation. The Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) trialled this approach in partnership with B&Q and two local authorities, who were responsible for marketing the scheme to the public. The scheme provided incentives in the form of price discounts to people who formed groups to bulk-buy these products. The more neighbours who signed up to buy together, the bigger the discount.

When governments get the idea that the public are idiots who can safely be patronised, maybe it’s high time the public nudged them out of office.

Stop emissions upstream – keep fossil fuels in the ground

A more effective way of reducing household carbon emissions would be to stop them upstream – at the point where they’re produced, for example by:

- cement, steel and other high-carbon manufacturers

- fossil fuel companies and

- fossil fuel energy companies that power the national grid

Large scale public investment in powering the grid by renewables – with adequate back up – would mean that people could heat and light their houses without producing carbon emissions. It would also create jobs, help develop new and more efficient technologies and help get us out of recession. But it would fly in the face of neoliberal doctrine.

Environmental activist Tim DeChristopher explains,

“In a hyper-individualised society, it is no surprise that climate action has been focused up to now on personal responsibility to limit consumption. We receive typically about three thousand adverts every day to consume, so green consumption bolsters that. The mentality is that the problem is one of individual and consumer habits, and that the answer to the climate crisis is lifestyle changes. This reinforces the idea that our primary identity is as a consumer, and reinforces a system that is the main problem. How can we recover and assert a system based on us as human beings rather than consumers?”

Are we citizens or consumers?

Given the neo-liberal ideology of the three mainstream political parties, it’s not surprising that UK climate change policies are geared to treating people as consumers, not citizens.

Rather than framing climate change as a political problem that demands political solutions, successive UK governments – New Labour & Coalition – have defined climate change as a problem caused by market failure, and urged a variety of ways for consumers to pay for mending this failure.

Trying to discipline consumers is a cop out. Worse, it’s punitive. It lets government off the hook of challenging the power of the new corporate feudalism and the old landed feudalism that, between them, are the root of the problem.

Our governments and their advisors suffer from a blinkered inability to see beyond the neo-liberal ideology that defines the world in terms of markets, a dominant financial sector and individualised consumers.

But this ideology is the problem that needs solving if we are to deal with and reduce climate change and other kinds of environmental – and social and economic – damage.