There is a public outcry in Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield about cost-cutting proposals to close and curtail acute and emergency hospital services and replace them with cheaper, integrated health and social care in the community (whatever that might turn out to be, because it isn’t at all clear).

People worry that, having downgraded the massively expensive Private Finance Initiative-funded Calderdale Royal Hospital to a small, planned care clinic with a minor injuries unit, the hospitals Trust would use the remaining three quarters of the hospital for private patients.

The proposals foresee 150 fewer acute and emergency beds for Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield patients – all in Huddersfield Royal Infirmary.

A psychiatric ward has already been closed some time ago, with the result that mental health patients have been sent all over England to wherever a bed is available.

People in Todmorden, at the far end of the valley from Halifax’s Calderdale Royal Hospital, already have long journeys to A&E. If Calderdale A&E closed, they would have to travel on to Huddersfield along a road notorious for its traffic jams.

Over the past few weeks, the public have attended marches and meetings to voice their alarm that lives will be lost as a result of longer journeys to Huddersfield A&E, while relying an already badly overstretched ambulance service.

Well aware of evidence that longer journeys to A&E are associated with higher death rates, the public asks how the ambulance service would cope with longer journey times if Calderdale A&E were to close.

The NHS bureaucrats haven’t bothered to ask this question. But everyone knows that Yorkshire Ambulance Service staff already work long hours without proper breaks. And the ambulance service can now only pick up certain categories of patients.

Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield NHS bureaucrats say everything will be fine, because there will be a new Minor Injuries Unit (MIU) in Todmorden – as well as one each in Halifax, Huddersfield and Holmfirth in Greater Huddersfield.

The public look at the list of treatments that a MIU can provide and disagree that this is an adequate replacement for Calderdale A&E department.

Public scepticism that cost cutting will improve patient care

The public don’t believe NHS bureaucrats when they say that this avowedly cost-cutting exercise will improve patient safety, through centralising acute and emergency care in one hospital with 24/7 consultant presence.

Nor is the public at all convinced that the loss of acute and emergency hospital services will be made good by replacing costly hospital services with cheaper integrated NHS and social care in the community – although the NHS bureaucrats trumpet this as being closer to people’s homes, supported by “virtual wards”, “locality teams” and “community hubs”.

This integrated care in the community is aimed at keeping three main categories of people with chronic and multiple health problems out of hospital:

- elderly people who may have complicated health problems and be near the end of their life

- people with long term “continuing care” needs because of non-communicable diseases such as cardio-vascular problems, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, diabetes, musculosketal problems, cancer, mental illness, kidney problems etc

- people who are judged to be statistically at risk of developing long term illnesses, either on the basis of their demographic characteristics (eg age, or living in a deprived area associated with health problems relating to poverty) and/or because of what their medical records show

There seems to be no reliable evidence that this will reduce costs or improve patients’ health.

There could be another, hidden, agenda: Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield’s “Right Care Right Place Right Time” (RCRPRT) proposals are a close fit with a new Big Pharma/Life Sciences business model that’s driving a global transformation of health and social care. The new business model aims to replace costly hospital care with cheaper healthcare in a “third place“ – neither hospital nor the GP practice, but wherever the patient happens to be – and it maps directly onto the RCRPRT proposals.

This isn’t surprising since Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield Clinical Commissioning Groups paid nearly £1m to PA Consulting, a management consultancy with a direct interest in this new business model, for “support” in developing the Strategic Review which underlies the RCRPRT proposals.

The Coalition government is promoting the new Big Pharma business model through its new Office for Life Sciences, under a Director from Deloitte, a global accountancy and corporate finance consultancy company.

The Better Care Fund

The Calderdale and Huddersfield Right Care Right Time Right Place proposals are vague about what integrated care might mean. They incorporate/ overlap with a compulsory country-wide plan for what was originally called the Integration Transformation Fund and is now called the Better Care Fund.

This is a national (English) £3.8bn fund that should transfer £1.9bn of NHS hospitals’ money and pool it with local authority spending on integrated health and social care in the community, starting in 2015. It follows on from the Coalition government’s five year transfer of NHS funding to local authorities that started in 2010.

Each English local authority and their local Clinical Commissioning Group have had to produce a joint plan that shows how they would spend their share of this £3.8bn Better Care Fund.

Councillor Tim Swift, Leader of Calderdale Council, said,

“There has been an incredibly tight timescale for agreeing a framework to make sure this money is available within Calderdale.”

This haste may be why the Cabinet Office recently held back the Better Care Fund scheme launch, scheduled for April 2014, on the grounds that there was no evidence that the policy would deliver the planned savings or introduce the proposed new system of patient care.

Despite the Cabinet Office’s delay of the launch of the Better Care Fund scheme,the DOH and DCLG deny that the Cabinet Office comments will have any effect on the release of funding for 1 April 2015.

It remains to be seen who will win this row and how it will affect the Right Care Right Place Right Time proposals.

Calderdale Council’s Chief Executive Merran Macrae has come down firmly on the DOH/DCLG side of the argument and denies that the Cabinet Office criticism will have any effect on Calderdale’s Better Care Fund plans – which NHS England (West Yorkshire) has told Calderdale Clinical Commissioning Group to tie in more tightly to the Right Care Right Place Right Time proposals.

The Calderdale Better Care Fund plan draws heavily on a Nuffield Trust report about the Kaiser Beacons pilot. This was a New Labour government project to trial the American private health care company Kaiser Permanente’s system of integrated care in the community.

The cost cutting agenda of integrated health and social care in the community

According to the Strategic Outline Case, one of the “key enablers” of the “savings opportunity” is job cuts – in its bureaucratic jargon it states:

“realignment of the current workforce to the revised model will impact on the number of people employed. Given 70% of costs currently relate to pay in order to achieve the level of savings required the overall paybill will need to reduce...”

Questioned about this, the Hospitals Trust Director of Workforce said that most of the

anticipated reduction in the wage bill will come from cutting the use of agency staff.

The bill for this has rocketed since the Trust cut staff in response to the need to make

efficiency savings.

The Strategic Outline Case (SOC) notes (p26) “significant potential shortages in the

health and social care workforce” and identifies “An expansion and increasing role for

an informal workforce of peer support workers and volunteers” as a key principle, taken

from the 2013 Kings Fund briefing paper NHS and Social Care Workforce: Meeting Our Needs Now and in the Future.

On p 22 the SOC says that

“Increased self-care will reduce the number of people needing to seek help from a health or social care professional”,

and on p 29 it says that self management and care will be the first option to be considered for patients being cared for in the community. Volunteer health trainers, peer support workers and expert patients will coach at-home patients in how to self-care.

“The approach will be to support individuals, families and communities to undertake activities that will enhance their health, prevent disease, limit illness and restore health.”

On p 29 the SOC also identifies volunteers and voluntary organisations as part of the

“locality teams” that would deliver community care.

Calderdale’s related Better Care Fund Submission (p9) outlines how at-home patients would rely on social care and support from volunteers from community groups, friends, family, and third sector groups (charities and social enterprises). On p11, Calderdale’s Better Care Fund Submission proposes a form of social needs assessment that

“reconnects people to their natural networks of support within their community and avoids the need for statutory health and social care assessment.”

This sounds like code for having people rely on family, friends and neighbours – what else are their “natural networks of support”? And why is it a good idea to avoid statutory assessment of people’s health and social care needs?

Another way in which patients would take more responsibility for their own care would be

through self-monitoring their symptoms using digital devices (so-called ‘telehealth’) to

measure blood pressure, heartrate, breathing, blood oxygenation and sugar, and so on,

depending on the patient’s illness. The outputs of these monitoring machines would be

automatically sent to specialist teams and would alert them if anything’s going wrong

with the patient’s health. Medical advice would be available via skype or phone

(so-called ‘telecare’).

But claims for the efficacy of telehealth and telecare are unsupported by evidence.

There is no definitive evidence that there are economic benefits or improvements in

outcomes at scale. Established and funded by the Department of Health, the Whole System Demonstrator programme was a randomised control trial involving over 6000 patients and 238 GP practices in three places in England (Cornwall, Kent and Newham).A 2013 BMJ paper found that,

“telecare as implemented in the Whole Systems Demonstrator trial did not lead to significant reductions in service use, at least in terms of results assessed over 12 months”.

An Upper Calder Valley Plain Speaker article on the Calderdale CCG contract for telehealth and telecare in care homes identified that industry lobbying lay behind the introduction of telehealth and telecare into the NHS, and the WSD trial.

The plans promise that there would still be face-to-face treatment and support in the home and in the neighbourhood – as nursing, physiotherapy, GPs, social workers etc. These health and social services would, we are told, be accessible at short notice in the patient’s home via so-called “locality teams” (groups of 5 to 10 GP practices).

Specialist kit in the home, for example mobility aids, would similarly be accessible via the “locality teams”. The locality teams would “align seamlessly” with private home care providers, community pharmacies, voluntary organisations and self-help groups.

There would also be two specialist community hubs that could bring together Minor Injuries Units with community and mental health services, diagnostics, pharmacy and social facilities.

However a GP has pointed out that, at least in the case of Todmorden – one of the proposed community hubs – all these services already exist, apart from the Minor Injuries Unit and social facilities.

The theory is that acute and emergency care in hospital would still be available, but used far less often and for shorter periods than at present, since the community care measures outlined above are intended to help patients to manage their health problems better so they wouldn’t have to go to hospital for acute and emergency care so often, and would be supported when they came home so they could leave hospital sooner. However, there is so far no reliable evidence that this happens in the real world.

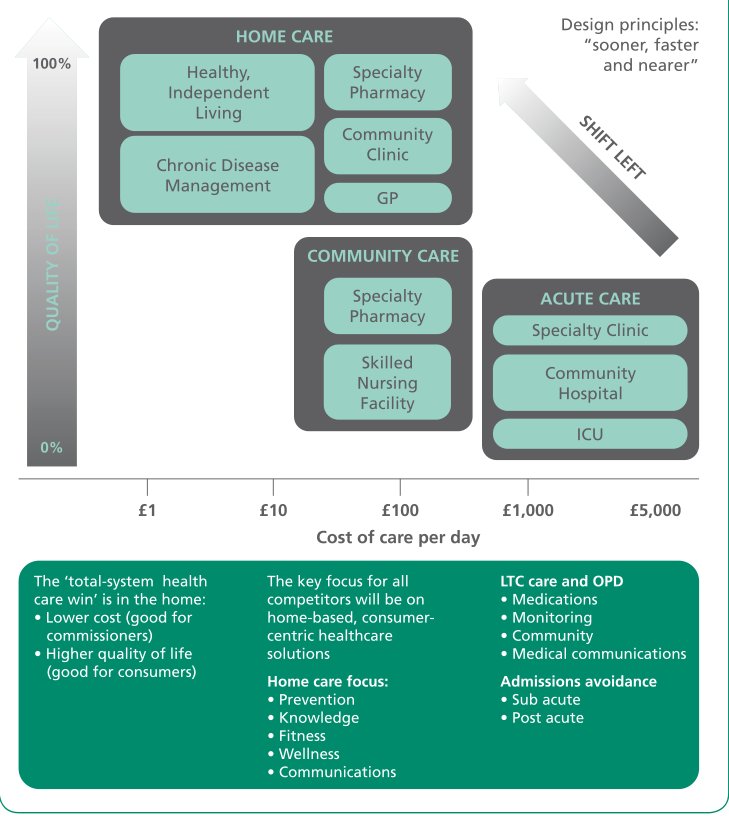

Some idea of the costs of this kind of system is given in a 2010 Nuffield Trust briefing – Removing Policy Barriers to Integrated Care. Comparing the costs of an integrated community health and social care system already set up in Nottingham with the costs of acute hospital care, the Nuffield Trust briefing showed that:

- The cost of home care to support “healthy independent living” and “chronic disease management” was between £1 and approx £30-40/day.

- The cost of “locality team” services – speciality pharmacy, community clinic, GP and skilled nursing facility – was between approx £30-40/day and £700/day.

- The cost of acute hospital care was approx £700-£5k/day.

These are 2010 figures, so the costs could be a bit higher now to take account of inflation.

But they show that if home care and community care keep patients with chronic illnesses out of acute hospital care (a big if, given the lack of reliable evidence), this should cut the costs of caring for such patients.

The integrated care in the community model therefore aims to shift as much care as possible out of acute hospital care, into far cheaper home care and community care.

Fig 1 Nuffield Trust briefing – Removing Policy Barriers to Integrated Care

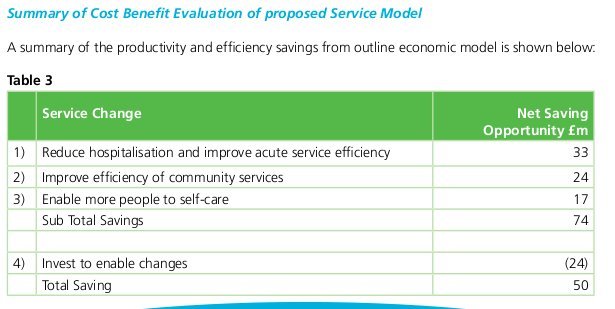

Table 3 SOC p 48 Productivity and Efficiency Savings from proposed service model

Privatisation, lower care standards, reduced wages and working conditions

The pro-privatisation agenda of the Strategic Outline Case is particularly clear in the section on social care provision in Calderdale. The Leader of Calderdale Council and members of the public who are social care users, carers and social workers have all roundly criticised this section for its inaccurate description of the current provision in Calderdale, and for its marketised vision of future social care.

The SOC states that Calderdale Council’s

“…traditional model of care and support is no longer sustainable and…encourages dependence…evidence indicates that people in Calderdale spiral into a cycle of dependency and escalating support needs.”

The Leader of the Council, Cllr Tim Swift, disagrees:

“This is not a fair description of how social care now operates in Calderdale. Our Vision for social care is clear about our twin aims of keeping people safe and promoting independence. Prior to approving this at Cabinet, there was very wide consultation with people who use services and the staff delivering them, and there is good evidence of the progress we are making. For example, Calderdale has the second best performance in the region in keeping people out of care homes until it is absolutely necessary. We have put a strong emphasis on investment in reablement services. Even in the current financial crisis, we have been able to keep eligibility criteria at moderate – if we were working in the way described in this document then we would no doubt have had to join the 88% of local authorities who have raised their criteria to substantial or critical.”

Social care users and social care workers have told Plain Speaker they think this SOC statement should be corrected when the full business case is written and the public is consulted on the proposals.

According to the SOC, Calderdale Council would no longer assess people’s social care needs but would give ‘information and advice’ to people who ‘will often make use of their own resources to self-fund care and support’. It would ‘create a responsive local market’ for social care and somehow ‘inspire and oversee care providers’ by a system of payments based on outcomes, eg keeping patients out of hospital.

This is echoed by the Better Care Plan, which states that Calderdale Council will avoid “statutory health and social care assessment” by releasing “health funding” – although the justification for this is unfathomable in the completely incoherent, ungrammatical sentence that this statement is part of.

These proposals seem to accelerate and intensify existing trends in social care. A social worker told Plain Speaker,

“Gone are the days when councils undertook in depth assessments and provided the appropriate services in house. It’s privatisation, services which have already gone to tender have lower care standards and rely on poor pay and working conditions. They are not monitoring providers of people who have personal budgets. Where is safeguarding in all this?”

Exactly how this fragmented, market-based approach to providing social care is supposed to benefit patients is not clear.

Alice Mill, a carer, said,

“I care for someone with cerebral palsy who finds managing his carers and finding an appropriate home equivalent to running a business.”

Why is it the business of local authorities and the NHS to create a local market in home and community-based care services?

The Better Care Fund plan and the SOC are full of phrases like ‘person-centred integration’. What this appears to mean is a plan to merge existing ‘personal social care budgets’, with new ‘personal healthcare budgets’ (PHBs).

Personal health budgets were first proposed by Labour peer Lord Darzi in 2008.

In 2009, the Royal College of Nursing warned that personal health budgets could be used to justify making cuts to community nursing.

PHBs were trialled in an inconclusive pilot.

The Coalition government slipped through the legislation for personal health budgets during a parliamentary recess in 2013, when MPs were on holiday.

The Dutch experience of Personal Health Budgets has been that they led to escalating costs and widespread abuse, with the result that the Dutch have radically reduced their availability.

In March 2014, the Nuffield Trust suggested that personal health budgets would require some NHS services to be scrapped and this would reduce patient choice.

Despite all this, the new system of PHBs, introduced on 1 April 2014, is now available to chronically ill patients living at home. They can use their PHB to buy in an agreed package of “continuing health care” services.

Patients can’t use personal healthcare budgets to pay for primary medical services such as care you normally receive from a family doctor, or for acute care services such as A&E. Instead, they are for specific aspects of ongoing care, such as psychological therapy or pulmonary rehabilitation package of care.

Calderdale Clinical Commissioning Group has told Upper Calder Valley Plain Speaker that it estimates around 60 patients in Calderdale are currently eligible for a personal health budget. This is out of a population of around 213,000. It seems a bit weird to design a whole integrated care in the community system around such a small number of people.

Personal health budgets are being rolled out to a limited group for now, but there is much enthusiasm to extend them. Worries are that it will undermine the example of universal, equitable healthcare. This is because individual CCGs will set the PHBs, so a postcode lottery is likely to occur.

And if patients want to buy extra continuing health care, on top of that provided for in their PHB package, they can do so privately out of their own income.

Patients’ use of their personal budgets would be key to the creation of a “local market” in home and community-based continuing care services, according to the SOC and Better Care Plan.

Patients in some parts of England can already buy needs assessments, social care and continuing healthcare services from online care marketplaces. Hertfordshire County Council has developed an online Care Market, in partnership with the cloudBuy company and Serco.

Northamptonshire County Council has also formed a partnership with cloudBuy and the consumer loyalty company Grass Roots, that is open to everyone who needs social care, not just social budget holders.

cloudBye and NHS Shared Business Services are launching a Care Marketplace service for the NHS and continuing health budget holders, which Greater Manchester CSU will pilot. This will allow the purchase of a range of continuing healthcare services, such as visits from a nurse, help with shopping or grip rails or other pieces of kit.

Somewhat weirdly, treatments purchased with PHBs do not have to be evidence-based treatments approved by NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

During a small scale PHB pilot in 2009, patients used personal healthcare budgets to buy things like theatre tickets, frozen meals and complementary therapies. These things are no doubt nice, but why should NHS funding be used to pay for them?

This seems to be part of a trend of poaching money from the NHS to spend on other services. It can only weaken the ability of the NHS to provide an effective, universal, equitable health service.

The clinical commissioning groups will pay for social care and continuing health care using a system of outcomes-based payments – for instance, success in keeping people out of hospital, “re-abling” people so they can return to work etc.

The trouble with this is that it provides a perverse incentive to avoid treating the most ill patients.

This is called “cherry picking” – limiting health care to commercially rewarding populations and neighbourhoods (ie people without long term illness and people living in middle class neighbourhoods where poverty-related, chronic health problems are rare).

At the 13th March Calderdale CCG Governing Body meeting, a GP warned that this

“…needs careful governance to avoid obvious cherry picking issues.”

“Virtual wards” in the community for people statistically at risk of hospitalisation

The plans put forward in Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield foresee the use of “risk stratification” and “predictive modelling”, using digitised data from patients’ GP and secondary care medical records to make a list of patients most at risk of emergency hospital admissions in the next 12 months.

Using this list, a multidisciplinary team based in a GP practice selects patients and admits them to a “virtual ward” – ie one that exists on the computer, not a real hospital ward.

There is so far no evidence about whether this model of integrated health and social care reduces rates of emergency bed use or length of stay. Although it has been trialled in a few areas, including South Devon and Torbay, a Kings Fund study says that evaluation for several years is needed to see what impact it has.

And in South Devon and Torbay, the 2013 Caldicott changes to information governance made it impossible to continue with “predictive modelling” as a way of drawing up the patient list. This is because of issues about Data Protection and patient consent.

The South Devon and Torbay GP practices now rely on “local intelligence” to admit patients to virtual wards.

Staff intensively assess the health of patients in this “virtual ward” and co-ordinate their home-based care, provided by various members of the multi-disciplinary team. Once patients’ health has stabilised they would be discharged from the virtual world.

In South Devon and Torbay the multidisciplinary teams are based in GP practices. Since March 2013 they have been paid for with a mixture of funding from NHS England and from Devon County Council, which has covered some of the social care costs for patients in the “virtual ward”.

But in South Devon and Torbay, increased workload in general practice and the community as a result of virtual wards has not been matched by an increase in staff and it has been difficult for community/multidisciplinary teams to attend all the monthly virtual ward meetings. Local authority investment in intermediate care has been a vital source of services and equipment in the community.

In April 2014, NHS England announced a new, one year Enhanced Scheme that will pay participating GPs a maximum of an extra £2.87/patient to introduce the use of risk stratification, putting at least 2 percent of their patients on a case management register of patients identified as being at risk of an unplanned hospital admission without proactive case management. This looks like a wider national trial of the virtual ward idea.

A GP poll in January found that only 51% of GPs were planning to sign up for the new Direct Enhanced System because of fears that it will consume huge amounts of practice time.

NHS Employers have issued guidance to GPs. GP Online reports the GPC deputy chairman Dr Richard Vautrey as saying:

‘GPs and practice managers need to be aware they need to maintain the 2% register throughout the year.

‘I think it is disappointing that this information has been issued at the 11th hour, or after the 11th hour. Practices wanted more preparation time, but there is now very little respite. Practices need to get on with developing registers to fulfill the requirements for the first quarter.’

Dr Vautrey said he hoped the process would not become a bureaucratic burden.

Practices will have until 30 June to sign up for the new DES.

The implications of this are unclear. Will GPs overloaded with admin really be likely to do this for next to no money? If not, will we see case management increasingly being handled by a ‘case co-ordinator’? Will they ever see patients on the virtual ward? Or will they just have patients’ data? Will they have any medical training? Or – behind the rhetoric of prevention (which is nothing new) – is this a way of shifting care away from a GP (inconveniently wedded to professional ethics, from the free marketeers viewpoint) to a non medically qualified administrator at the end of a phone line, much like in the US style insurance model?

Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield plans also include targetting behaviour change initiatives at people whose demographic profile suggests they are statistically likely to develop chronic illnesses. This could be because of their age, for example, or because they live in a deprived area with high incidences of ill health related to poverty.

Behaviour change schemes would try to incentivise people to adopt a lifestyle that involves eating healthy food, exercising more and smoking and drinking less.

They do not address the wider social and economic structures and conditions that create deprivation and poverty.

The Case for Change – all about saving money, not about patients’ needs

The Strategic Outline Case says that the “case for change” is based on the need to cut NHS and social care costs by £160m over the next five years in Calderdale and Huddersfield.

However, this figure seems to be cast into doubt by the Strategic Review Executive Steering Group Meeting on 20th February 2013, which came up with a rather different picture of the Baseline financial data, produced by PA Consulting Group together with the CCGs’ Directors Of Finance:

- current system spend is £1.7bn

- the 7 organisations (NHS organisations and local authorities) have to save £303m (“a combined savings challenge”, with commissioning having to save £124m. These are all one year figures.)

- “It was agreed the commissioners’ figure of £124m would be talked about”

Whatever the true “savings challenge”, the SOC “case for change” focuses on the NHS providers’ needs. The basis of the SOC economic model is to provide cheaper health care – not an assessment of the health needs of the population or an assessment of how the proposed reconfiguration affects people.

The assessment of the impact of the SOC reconfiguration on local people is one-sided, identifying only benefits and ignoring possible costs and risks. The benefits it identifies are often questionable and the impact assessment gives a strong impression that it has cherry picked examples of benefits without too much concern for accuracy or truthfulness.

Although planning for this has been going on for 2 years, there is no clinical evidence to support the proposed reconfiguration.

According to a regulatory lawyer’s guidelines on NHS reconfiguration published in Guardian Healthcare, putting NHS provider needs first as the basis for the case for change may violate legal regulations about NHS reconfigurations. The Calderdale and Huddersfield campaign group, Band Together for our NHS, is taking legal advice about his and other possible breaches of NHS regulations.

Dodgy Evidence

The Strategic Outline Case relies on dodgy evidence to justify its proposals for the future of the NHS and social care in Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield.

All too often its evidence comes from the pro-privatisation think thanks and management consultants that the Department of Health and NHS England have effectively outsourced policy making to. Their suggestions are built on sand.

First off, there seems to be no reliable evidence that integrated health and social care in the community cuts costs or improves patients’ health.

Second, claims that an aging population is overloading the NHS in its current form appear to be unfounded, despite Jeremy Hunt’s statement that this is

“a challenge more serious than the economic crisis…potentially even as serious as global warming”

Like so much else in the proposals to “transform” the NHS, this seems to have originated with the American management consultancy company McKinsey in 2009, when they interwove “demographic time bomb” rhetoric with the “funding gap” rhetoric.

A review of studies of the effects of an aging population on healthcare costs concludes otherwise:

“On the whole, there is… a small positive effect of aging on per-capita health expenditure, which several studies estimate to be in the order of an annual growth rate of 1.5%.” (Friedrich Breyer, Stefan Felder, Joan Costa-i-Font, 14 May 2011)

This is because people aren’t just living longer, they stay healthier for longer. And although there is a small increase in health care spending because of them, older people contribute a massive amount to the economy, in terms of both waged and unwaged labour.

Ignoring this evidence, the rhetoric of apocalyptic demography serves a neoliberal agenda of cuts to public services.

Third, to the extent that the NHS is under pressure from an aging population, this is the result of austerity politics in the shape of cuts to social care funding since the recession.

Research carried out by the LSE found that social care funding cuts have left half a million older and disabled people, who would have received social care five years ago, without support. The number of people receiving social care has plummeted for five years in a row – by a total of 347,000 since 2008. This has put huge pressure on the NHS.

Fourth, claims for the efficacy of telehealth and telecare are similarly unsupported by evidence. There is no definitive evidence that there are economic benefits or

improvements in outcomes at scale. Established and funded by the Department of Health, the Whole System Demonstrator programme was a randomised control trial involving over 6000 patients and 238 GP practices in three places in England (Cornwall, Kent and Newham).A 2013 BMJ paper found “telecare as implemented in the Whole Systems Demonstrator trial did not lead to significant reductions in service use, at least in terms of results assessed over 12 months”.

An Upper Calder Valley Plain Speaker article on the Calderdale CCG contract for telehealth and telecare in care homes identified that industry lobbying lay behind the introduction of telehealth and telecare into the NHS, and the WSD trial.

Fifth, the Right Care Right Time Right Place proposals claim to be driven by the need to curb rising healthcare costs, but they fail to address the causes, which include:

- growing inequality, leading to poverty-related illness

- regulatory capture of government by junk food companies and alcohol companies

- market incentives for medical overtreatment

Recently a lobbying company working for some of the world’s biggest drugs and medical equipment companies wrote a draft report which could help shape NHS policy.

Big Pharma’s bonanza of overtreatment costs patients dearly, in terms of adverse drug reactions. A Better NHS blog by Dr Jonathan Tomlinson points out:

“The numbers of prescriptions issued are rising dramatically…on average people over 60 received more than 42 prescription items per head in 2007 compared to an average only just over 22 in 1997. Hospital admissions for adverse drug reactions (ADR) are increasing substantially and particularly so in the elderly . Between 1999 and 2008 the annual number of ADRs increased by 76.8%.”

The use of risk stratification will lead to attempts to get people to undergo diagnostic tests for health problems they are deemed statistically likely to develop, even if they are quite healthy and symptom-free.

The new Big pharma/life sciences business model which is driving the transformation of NHS and social care in the Right Care Right Place Right Time proposals seems to be about turning our bodies and our minds into cash cows for new hybrid business interests, that combine BigPharma with digital/ social media technologies and companies.

To find out about the pro-privatisation think tanks and management consultancy companies behind the plans to transform the NHS, please see this Plain Speaker article

This is the link to Choosing a predictive risk model – guide for commissioners -pdf

The obfuscation of what’s really happening is alarming. Euphemistic labels for future “care” would be laughable if they weren’t so sinister.