Hydrology is a science dealing with water on the surface of the land, in the soil and underlying rocks, and in the atmosphere. Most people will probably have vague memories of learning about the water cycle in GCSE science classes – here’s what it looks like

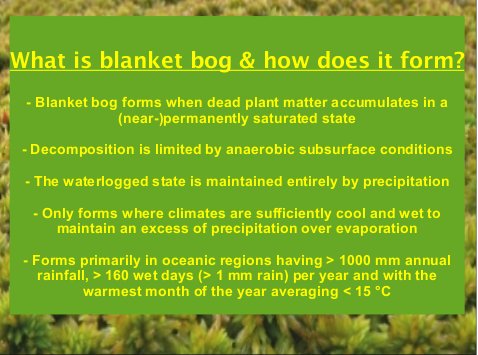

Blanket bogs are of great importance in the water cycle in their areas. Slides 7 – 11, below, are about blanket bogs and their role in the water cycle – particularly in reducing the risk of flooding.

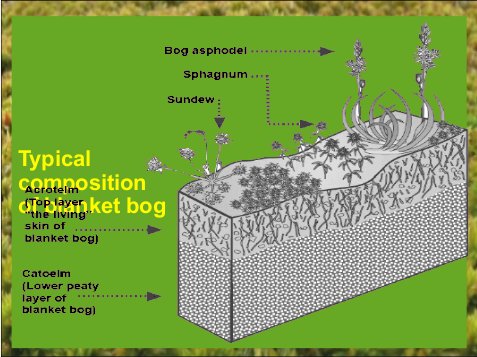

The background to all these slides is a photo of healthy sphagnum moss. There’s information about this in the slides on blanket bog composition, three slides down from here.

The development of Blanket bog started to form in the Pennines about 8,000 years ago, when a period of increased rainfall led to the death of the woodlands that grew on these upland areas, and their replacement by newly-forming blanket bog and peat. A leaflet on the Peatlands of the North Pennines explains

“For several thousand years the blanket bog flourished. Layers of dead Sphagnum, grasses and heather built up in the wet acidic conditions, forming peat at a rate of about 1 mm per year. Over the past 1,000 years more intensive use of the upland landscape has had an impact on our peatlands. In recent centuries particularly, drainage, grazing and moorland burning has left a legacy of drying and eroding peat.”

Which is the state they’re in today on Walshaw Moor.

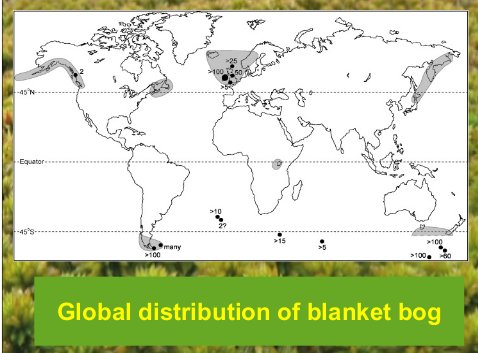

Blanket bogs are an important carbon sink – they hold a lot of carbon in their peaty layers. 15% of the world’s blanket bogs are in the UK, so threats to their integrity are a potential positive feedback to global warming. If they are damaged, they tend to release carbon back into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, which is a greenhouse gas. This then contributes to further global warming. There is also evidence that damage from burning increases the amount of dissolved organic carbon flowing into rivers, and that this may turn upland peat from a net carbon sink into a carbon source. (Yallop & others, 2010. Increases in humic dissolved organic carbon export from upland peat catchments.)

In contrast, restoring them can radically reduce carbon emissions to the atmosphere. A briefing on Peatlands and Climate Change from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) UK Committee points out that

“Delivery of the UK Biodiversity Action Plan target to restore 845,000ha blanket bog by 2015 could bring emissions savings of 1.5 million tonnes carbon dioxide per year.”

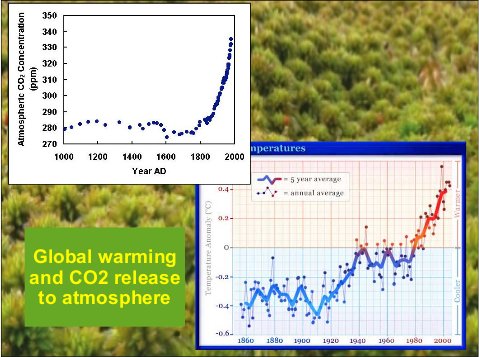

These two graphs in the slide above show how increases in the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide have shot up since the start of the industrial revolution, which was driven by burning fossil fuels, and how the earth’s average surface temperature has risen more or less in step with this. There’s some information about climate science here.

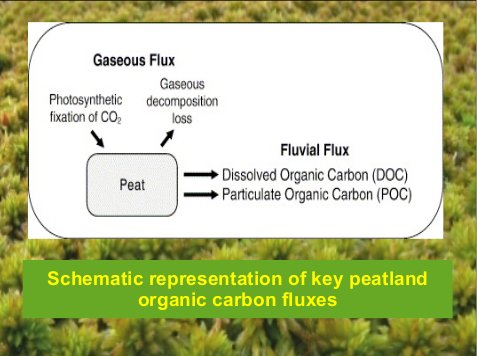

A carbon flux is the transfer of carbon between different carbon “pools” – either in the atmosphere, soil or water. Blanket bog plants take carbon dioxide from the air during photosynthesis, and when they die and accumulate in the peat bog, the peat bog holds and stores the carbon. This is a gaseous flux, because it involves the transfer of carbon between the atmosphere/air (where it takes the form of carbon dioxide gas) via plants (where photosynthesis turns carbon dioxide into carbohydrates) into the bog. The fluvial (river or stream) flux involves the transfer of carbon from the peat to rivers and streams.

(Info source: Yallop & others, 2010. Increases in humic dissolved organic carbon export from upland peat catchments.)

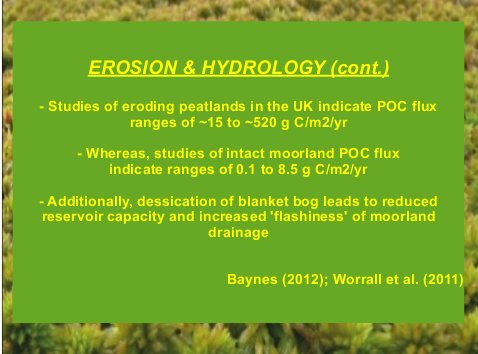

Particulate organic carbon is particles of peat carbon.

The “connectivity of a hydrological system” means the speed with which water flows through a local water cycle. In terms of blanket bogs, if they’re drained and burned, they dry out and this makes heavy rainfall flow through them quickly, contributing to flooding in nearby rivers and streams. This is the same thing as the “flashiness” of moorland drainage in the next slide, below. Flashiness as in flash floods.

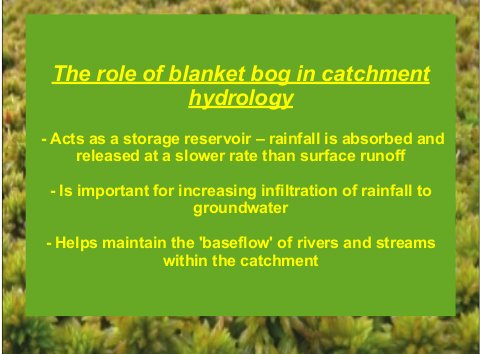

A catchment area is the area around a river or stream, where rainfall which lands there drains into the river or stream. Healthy blanket bog holds the water so it doesn’t run off the earth’s surface. This lets the water percolate gently into the ground so the ground holds more water and the water table rises. This helps keep the rivers flowing even when there’s no rain – this flow is called the “baseflow”. Walshaw Moor is the catchment for Hebden Water, which flooded very badly in June this year.

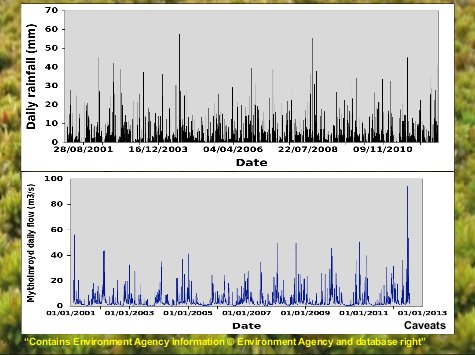

This slide shows the relationship between rainfall and the flow of the River Calder at Mytholmroyd. I’m not sure of its significance – it’s something to do with showing the baseflow in relation to increased flow when it rains. I’ll find out and post more – or if anyone reading this knows more, please leave the info in the reply box at the bottom of the page.

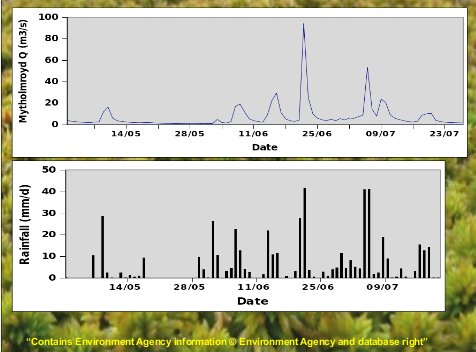

This slide shows the rainfall and the river Calder flow just before and during both lots of flooding this summer.

Precipitation = rainfall, snow, hail – water which falls from the clouds. So, as climate change happens, it’s likely to rain more here, with extreme rainstorms like we’ve had this summer. This makes restoring the blanket bog even more important – first, to reduce the risk of Hebden Water flooding, second, to keep the carbon locked up in the peat so it doesn’t return to the atmosphere and drive more climate change.