Midway along his life’s path, George Monbiot found himself on a dreary moor with no track to show him the way.

Lacking a poet ghost to guide him on the necessary descent into the circles of hell, through purgatory and on to paradise, Monbiot’s new book Feral conjures an Edenic fantasy of re-forested uplands, prowled by wolves, beavers and other top predators. In his dreams, he has banished the pesky sheep and hill farmers who between them have degraded this once and future biodiverse ecosystem.

Most likely these ecologically boring moorlands are a projection of Monbiot’s own middle aged tedium. If all the world and love were young…

And this is what Monbiot aspires to: a restoration of ecosystems that prevailed when all the world was younger than it is now.

Feral: the high concept

This is not a review of Feral, since the book has not yet arrived in Hebden Bridge Library and I’m not on the list of people Penguin sends review copies to. Instead, this is a look at the publicity campaign’s high concept.

Monbiot’s appearance on Newsnight showed him in puckish mode – if no longer an enfant terrible, a middle aged man terrible. Advocating the end of hill farming, Monbiot denounced hill farmers and their sheep for cropping the uplands to a monoculture of grass and heather as featureless as bowling greens.

A lightning costume change saw him zip into Nasty Party robes, demanding a stop to Common Agricultural Policy subsidies to hill farmers. This would soon see them packing up their quad bikes and crooks and sending their last sheep to market. Problem solved, according to Monbiot. A Sussex sheep farmer disagreed. Monbiot smiled through her comments with a noticeably stiff upper lip.

Well, quite entertaining, but since Monbiot was playing the superannuated enfant terrible card, not possible to take seriously.

Elsewhere, it seems that he is serious. A Big Issue interview with writer Robert Macfarlane finds Monbiot explaining that his embrace of rewilding originated in a mid-life crisis of boredom – “…the thrills I sought were limited in ecosystems as depleted as ours.” Neither writer considers the hubristic aspect of proposing to knock hill farmers out of a job and re-engineer whole ecosystems, as a way of working through middle aged boredom with your life.

A chapter of Feral published on the Aeon website gives a taste of the book itself. Monbiot’s writing here is much better than his talking. (That’s why he’s a writer, duh.) This chapter takes readers on a road trip through an area of Slovenia that has rewilded itself since the political tragedy of Nazism and its fallout rendered the land uninhabitable, depopulating its sheep- and goat-farming hills.

While Monbiot is lyrical about the experience of driving and walking through lush forest in the tantalisingly glimpsed company of top predators, he is clear that, like most rewildings, this is the result of human tragedy. And here’s the rub.

Rewilding: flavour of the moment in conservation circles

My son Sam, who has just finished the undergraduate Outdoor Studies (Environment) course at Cumbria University, says rewilding is flavour of the day in conservation circles, with many conservationists now thinking it should be encouraged where possible.

Rewilding aims to reintroduce top predators that have become extinct because of human intervention. Predation experts say that in ecosystems that were once ruled by top predators, their extinction has led to the decline of the whole ecosystem (a trophic cascade). Reintroducing top predators should enable ecosystems to function properly again, restoring biodiversity.

Newer information about the processes of ecosystem formation may cast doubt on this theory.

The WWF promoted rewilding in Europe at the end of the 1990s, as there was a lot of abandoned farmland where top predators could be reintroduced. But recent global food shortages (partly due to land grabs in Africa, Asia and Latin America to grow agro-energy crops for Europe and North America, and partly due to financial speculation on food prices) have caused anxieties about European food security and the need to bring farmland back into production.

Green grabbing

This is not the only reason why rewilding’s a contentious concept. Perhaps more importantly, it can be seen as an example of the growing practice of green grabbing.

An article in the Journal of Peasant Studies defines green grabbing as “the appropriation of land and resources for environmental ends” – whether for biodiversity conservation, biocarbon sequestration, biofuels, so-called ecosystem services, eco tourism or ‘offsets’ related to any or all of these.

Green grabbing transfers “ownership, use rights and control over resources that were once publicly or privately owned – or not even the subject of ownership – from the poor (or everyone including the poor) into the hands of the powerful.” Monbiot’s tightlipped Newsnight advocacy of clearing the uplands of hill farmers surely fits this bill.

Green grabbing is part of the growing commodification of nature, under the greenwashing rubric of sustainability, conservation or green values. Rewilding Europe identifies business interests as a key to nature conservation, through the new pricing of ‘ecosystem services’ like clean water, air, carbon sinks etc. “Naturally functioning ecosystems… have great intrinsic economic value.” “ …the new nature manager is an entrepreneur.” This is part of the contentious ‘natural capital’ movement that aims to bring all aspects of ecosystems into the market system.

Since the operations of the market system have resulted in environmental depredation, Einstein’s comment about the madness of trying to solve a problem by repeating the actions that caused it is surely applicable here.

Agroecology

One possible answer to the problem of how to restore biodiversity to UK uplands is not rewilding, but agroecology. Incredible Farm in Walsden and Incredible Edible Mytholm in Hebden Bridge are in the early stages of researching the possibility of setting up an experimental agro-ecology farm on the tops above the Upper Calder Valley.

We are interested in extending existing small scale experiments, carried out by individuals living on the tops, which have created fertile microclimates through judicious tree planting that provides shelter for a variety of crop farming. We think that agro-ecology offers a possible human-scale set of solutions to a number of problems that include, but are not limited to, the need to restore biodiversity and to escape the boredom that comes with alienation.

Growing old: a great alternative to being dead

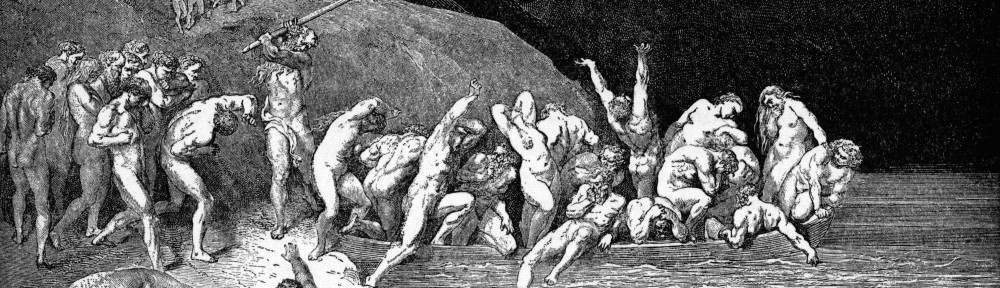

Let’s face it. If we’re lucky, we grow old. Dancing with wolves, bears nor lynx will not rejuvenate us. The old spirit guide for a way out of the trackless wastes of our midlife crisis has downed tools – Virgil seems to have quit his job, no doubt exhausted by the labour of guiding Dante out of a dark wood.

And how ironic that Dante’s image of his midlife crisis was precisely the forest that Monbiot yearns to find himself in. Perhaps what Monbiot really wants, like so many other greens, is a return to the middle ages.

Whatever. We can find inspiration in another writer who, like Monbiot, has appeared on Newsnight. When Jeremy Paxman asked how she felt about being seventy, Alice Walker said, “It’s a great alternative to being dead.” And laughed.

As is only fair, here is Monbiot’s reply:

@lastbid It would have been so much better if you’d read the book first, as you’d find most of your questions and points have been answered.

— GeorgeMonbiot (@GeorgeMonbiot) June 7, 2013

a very interesting and entertaining article Jenny. I’m particularly intrigued by the concept of green grabbing, which I hadnt come across before. I also write a blog about nature, politics and the like, and have blogged many times about re-wilding – I am not a great fan either.

cheers

Miles