Biofuel -also known as agrofuel- is one of those ideas that seemed great at first. Bio-diesel from soy oil or palm oil, and bio-ethanol from sugar cane, beet, wheat and corn sounded like good alternatives to the fossil fuels we use for transport and electricity generation.

But since we first starting hearing about biofuels, their drawbacks have become clear. In 2011, the Nuffield Council on Bioethics reported that:

“current UK and European policies encourage unethical practices”.

The Council called for new biofuel policies, founded on:

“a comprehensive ethical standard for all biofuels developed in and imported into the EU, enforced through a certification scheme….based on the following ethical principles:

- Biofuels development should not be at the expense of human rights

- Biofuels should be environmentally sustainable

- Biofuels should contribute to a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions

- Biofuels should adhere to fair trade principles

- Costs and benefits of biofuels should be distributed in an equitable way”

UK biofuels policy

The main UK law that applies to transport biofuels is the Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation (RTFO) Order. All suppliers of transport fuels who supply at least 450,000 litres of fuel a year, must show that a percentage of road transport fuels that they supply in the UK come from renewable sources and are sustainable – or, that they pay a substitute amount of money.

Following the Nuffield Council on Bioethics report, the UK Coalition Government carried out a consultation about the UK’s biofuel policy. It then amended the Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation (RTFO) Order – in line with the European Union’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED), biofuels now have to meet mandatory carbon and sustainability standards in order to qualify for Renewable Transport Fuel Certificates (RTFCs), which show that transport fuel suppliers comply with the RTFO.

It’s too bad that these changes to the RTFO law don’t effectively stop biofuels’ negative impacts on the environment and people.

There is an Early Day Motion calling on the government to to remove the existing financial incentives for biomass and bioliquid electricity in the Renewables Obligation when the forthcoming review of banding is implemented in April 2013, so that this support can be directed towards other renewable energy sources.

Biofuels have three main negative impacts.

Landgrabs and the threat to food and energy sovereignty and biodiversity

It’s impossible for the European Union to meet its targets for the use of biofuels from energy crops grown in Europe. This wouldn’t leave enough land to grow food. So instead, European and multinational agribusinesses are grabbing land in the South – land where traditional farmers have been growing food.

This photo is from a Guardian article on biofuel evictions

Farming families evicted for biofuel plantation face the security forces in Guatemala’s Polochic valley, March 2011. (Faces and clothes have been obscured to protect identities) Photograph: Campesino Unity Committee/Oxfam_from Guardian article.

This creates hunger in traditional farming communities that no longer have land to grow enough food, and drives up food prices because of the resulting food scarcity. These food price rises create more hunger, because people can’t afford to buy expensive food. But these people are powerless. They can’t vote out European MEPs or riot in European streets, to bring an end to the laws that require biofuel to be mixed with diesel and petrol.

This is a major example of environmental injustice. A report on Food & Energy Sovereignty Now points out that:

“Governments of the North, with their strong support for biofuels, are avoiding the political (and societal) burden of tackling the basic root cause of climate change, which would dramatically impact the lives and lifestyles of their citizens.Above all, governments are avoiding challenging corporations…”

Biofuel monoculture plantations also threaten biodiversity – for example, oil palm plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia are threatening to make orang utans extinct. And although biofuels are classified as renewables, their cultivation depletes the soil and water supplies – resources which, once exhausted, are not renewable.

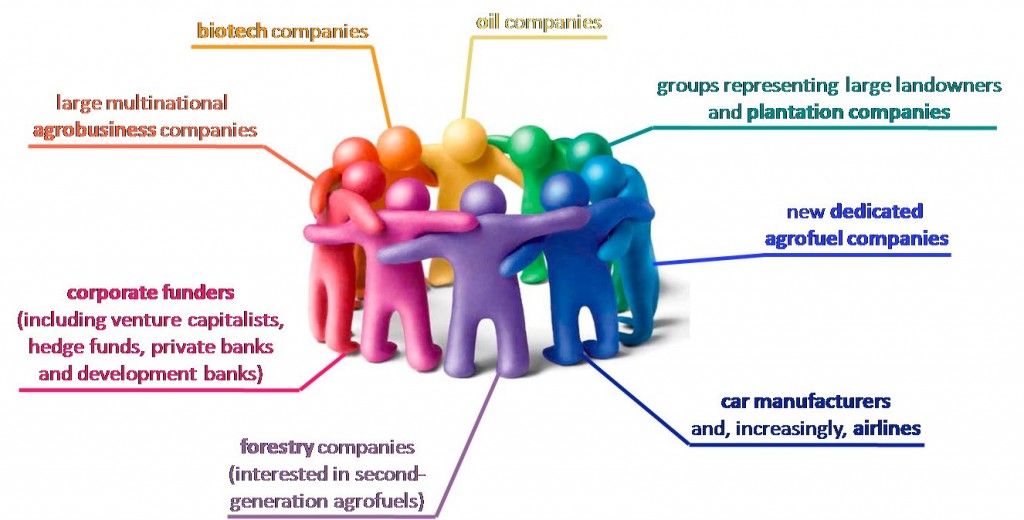

New agroenergy sector is profiteering from climate change

The expansion of biofuel crops in countries in the South is controlled by US and European corporate agro-industry giants, in pursuit of a market created by USA and European Union policies that require biodiesel and bioethanol to be used in transport fuels.

The growth of biofuels brings together two powerful corporate sectors. Global agro-industry corporations and fossil fuel energy companies are forming a new, powerful, corporate agro-energy sector.

The agrofuel sector continues to feed the kind of resource-intensive production and consumption that’s the cause of climate change. So it’s hardly likely to reduce climate change.

And while the ostensible aim of biofuels policies is to reduce carbon emissions from the transport sector, in fact biofuels increase carbon emissions.

It seems likely that in many cases, such as the 2007 USA/Brazil agreement on biofuels (Memorandum of Understanding Between the United States and Brazil to Advance Cooperation on Biofuels), a more important policy aim is to use biofuels to drive so-called “free trade” agreements. The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Human Development Report 2007-2008, Fighting Climate Change: Human Solidarity in a Divided World, advocates removing tariffs on the import of Brazilian ethanol into the USA, and advocates boosting international trade as a way of reducing carbon emissions.

This reliance on “free trade” under the terms of the World Trade Organisation is a way of increasing the power of the multinational corporations that dominate world trade. This dominance has involved the creation of Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights, which allow corporations to assert their “copyright” over a growing range of natural resources, including seeds and other genetic material. So “free” trade is in fact anything but.

This neoliberal policy also points the way towards climate change reduction strategies that rely on corporate-controlled global emissions trading and carbon credits trade. These – will have all the problems associated with the expansion of a poorly regulated financial sector. This corporate-controlled policy fails to address the causes of climate change, and amounts to corporate capture of political discourse and decision making.

Corporate capture of government powers has been growing since the 1970s debt crisis (sound familiar?- what goes around comes around).

Following this debt crisis, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund imposed “structural adjustment programmes” on debtor countries. These programmes were based on so-called “Washington consensus” economic policies, that Naomi Klein has described in her book Shock Doctrine.

The Washington consensus required debtor countries to deregulate and privatise their economies and accept neo-liberal international trade policies that meant:

- slashing their import tariffs, which had protected their own industries

- opening their markets to foreign goods and investment

- committing their best land and financial incentives to producing food for export, primarily to rich Northern markets.

The effects include:

- the transfer of wealth to global corporations – six corporations now control 85% of the global trade in grains

- creating food scarcity in countries that are major food exporters – millions of people go hungry in a condition of abundance

- turning countries that were previously self-sufficient in staple foods into importers of food staples, eg Haiti used to grow enough rice for its own needs, but since the trade “liberalisation” policies kicked in, requiring it to slash its rice tariffs in 1995, it has to import 82% of its rice.

So-called “free trade” rules in fact work to the advantage of global corporations, and the rich countries that dominate the World Bank, IMF and World Trade Organisation. This is a long way from the Nuffield Council on Bioethics recommendations that:

- “Biofuels should adhere to fair trade principles

- Costs and benefits of biofuels should be distributed in an equitable way”

According to the Oakland Institute report, Food Crisis and Latin America,

“Unfair global trade rules systematically place most Latin American producers at a disadvantage while continuing to benefit Northern producers. Trade rules promoted by the World Trade Organization (WTO), World Bank, and the IMF allow rich countries’ agriculture subsidies to artificially depress the prices of foods such as corn and wheat. In the U.S. and in Europe, agricultural subsidies are granted to farmers according to the quantity of commodity crops produced, which floods the market in commodity crops and drives down the global price. The EU channels nearly $100 billion dollars a year to its farmers in subsidies under the CommonAgricultural Policy (CAP), and the United States, nearly $50 billion a year under the US Farm Bill. This puts Latin American farmers at a disadvantage for two reasons. One, developing country farmers cannot compete with these artificially depressed prices. Two, removing tariffs in developing countries and approving international trade agreements has meant that rich nations such as the U.S. are able to dump their heavily subsidized surplus crops in developing countries, thereby destroying their agricultural base and undermining local food production.”

The power of the World Trade Organisation is shown by the fact that, although the UK Coalition Government has seen the need to impose mandatory carbon and sustainability standards on biofuels, it is unable to block imports of biofuels that don’t meet those standards. All it can do is categorise them as fossil fuels – but it still has to allow the fuel suppliers to import them, regardless of the environmental damage, human rights abuses or creation of food shortages that their cultivation has caused.

Biofuels can increase carbon emissions

The growing use of palm oil as biodiesel, and as a fuel for electricity power generation, is driving deforestation in tropical countries like Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. And in Brazil, most biofuel comes from soy, a key cause of deforestation in the Amazon, and from vastly expanded sugar cane cultivation, which is also responsible for introducing monoculture plantations that destroy bio-diverse ecosystems.

Deforestation is a direct consequence of European Union, US and Canadian regulations that require minimum biodiesel content in petrol and diesel. These regulations drive the increasing demand for palm oil and soy biodiesel, leading to forests being cut down to provide space for palm oil plantations.

Deforestation is a big source of carbon emissions and climate change, since the forest carbon sinks which have absorbed atmospheric carbon dioxide are lost. Oxfam estimates that these EU regulations could raise carbon emissions from deforestation by up to 4.6bn tonnes of CO2 – more than 70 times the CO2 savings the EU expects to make from reaching its target of deriving 10% of its transport energy from biofeuls by 2020.

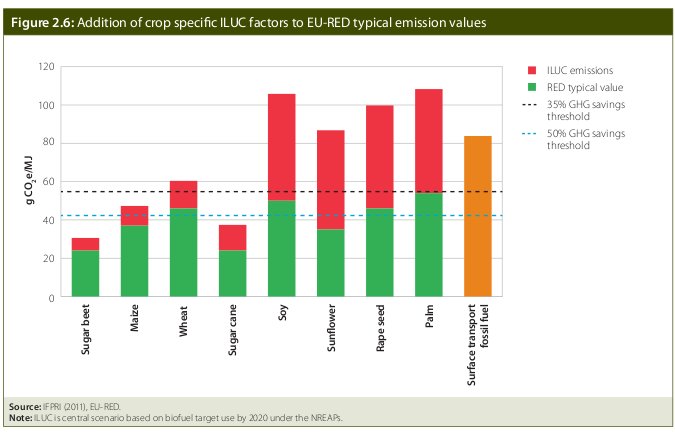

This diagram shows the greenhouse gas emissions of different types of biofuels – including greenhouse gas emissions from indirect land use changes (ILUC) caused by growing biofuel crops. An example of indirect land use change is when people have to use other land to grow their food crops, because biofuel plantations have driven them off the land where they used to grow their food. The diagram shows that soy, palm oil, sunflower and rapeseed oil emit more greenhouse gases than surface transport fossil fuels.

This diagram shows the greenhouse gas emissions of different types of biofuels – including greenhouse gas emissions from indirect land use changes (ILUC) caused by growing biofuel crops. An example of indirect land use change is when people have to use other land to grow their food crops, because biofuel plantations have driven them off the land where they used to grow their food. The diagram shows that soy, palm oil, sunflower and rapeseed oil emit more greenhouse gases than surface transport fossil fuels.

A new report commissioned by Action Aid and Friends of the Earth finds that biofuels policy would increase carbon emissions, not reduce them. The report says that it would be better for people and the environment if money that is spent on biofuels, were used to improve public transport, make cars cleaner and make it easier and safer to cycle.

The UK Climate Change Committee’s 2011 Bioenergy Review says,

“The sum total of cultivation, production and transportation emissions and land use change impacts means that overall emissions savings from bioenergy crops (food and fodder and dedicated energy crops) to meet near-term targets for liquid biofuels are highly uncertain and could be very low or even negative.”

EU biofuels policy’s based on now-discredited information

This is the view of the EU Climate Commissioner. She says the EU policy that requires European transport fuel to include 10% sourced from biofuels is out of date, based on now-discredited information.