Kirklees and Calderdale people are very upset about the proposed hospital cuts and changes and A&E closure – but related proposals to move hospital services into the “community” are equally devastating.

Care Closer to Home is part of the wider plan to cut hospital services – including closing Huddersfield Royal Infirmary A&E. Together, the hospital cuts plans and the Care Closer to Home plans go under the name of Right Care Right Place Right Time.

(Except in North Kirklees where they go under the name of Meeting the Challenge, and have already been underway for a couple of years.)

The contentious “Right Care” scheme includes the proposal to:

- Knock down HRI, sell the land and replace the existing 400+ bed District General Hospital and A&E with a 119 bed planned care hospital, on the Acre Mill site across the road, (serving both Calderdale and Kirklees), and an urgent care centre (no A&E) for Kirklees.

- Expand Calderdale Royal Hospital to around 600 beds and make it the acute hospital for both Calderdale and Kirklees, with the only A&E – except it won’t be an A&E, it’ll be an Emergency Care Centre. And Kirklees patients who need emergency care won’t necessarily be taken there.

The Care Closer to Home scheme has the potential to wreak destruction on the bit of the NHS that most of us use more than anything else – our GP/primary care services.

Speaking at a recent meeting of Save the NHS campaigners with the Shadow Secretary of State for Health, a representative of the National Pensioners’ Convention quoted an NHS staff member who works in a community-based End of Life service:

“We are passionate about giving a good service, but there are not enough specialists, not enough nurses, no spare capacity to train. Patients will suffer.”

She also quoted a mother (and carer) of a patient who uses a community-based mental health service:

“My daughter is being pushed to independence as they don’t have the capacity to treat her now. As a result, she tried to commit suicide – no counselling, just sent back home for us to try to pick up the pieces.”

Based on information drawn from the Right Care Right Time Right Place Pre Consultation Business Case (PCBC) – and from other sources, as the PCBC is full of holes – Plain Speaker tries to begin to answer some key questions about so-called Care Closer to Home.

This is Part One and it covers:

- What is Care Closer to Home?

- Why are GP services in crisis and what has this got to do with Care Closer to Home?

- Whose idea is Care Closer to Home?

- Which patients would be affected?

There will soon be links to Part Two and Part Three, which cover other aspects of the Care Closer to Home scheme.

What is Care Closer to Home?

Phase 1 Care Closer to Home (which has already happened) was about re-specifying existing community services.

Phase 2 Care Closer to Home (CC2H) plans to move a number of services out of the Huddersfield, Halifax and Dewsbury hospitals “into the community”, in order to cut costs of so-called “avoidable emergency admissions conditions”.

In other words, people going to A&E because of illnesses and frailty that wouldn’t have got so bad if they’d been better looked after.

Never mind that there’s no evidence that these Care Closer to Home services can replace A&E or that there’s the money to pay for them

On p 136 of the Pre Consultation Business Case, the Clinical Senate (a group of doctors not connected with the Calderdale, Kirklees and N Kirklees Care Closer to Home scheme) says that that these Community Services Specifications lack information about

“whether the care closer to home vision is achievable financially”.

The whole Right Care Right Place Right Time programme is based on making so-called “efficiency savings” (ie cuts), in order to avoid a projected £281m funding shortfall for Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS which would open up by 2020/1, given the government’s spending plans, if current services continued to be provided.

The government’s miserly and mean spirited spending plans are a political choice, not an economic necessity. We are the sixth richest country in the world, we are wealthy – but we spend a far lower proportion of our national wealth on the NHS than comparably wealthy countries spend on their health services.

Never mind that a review of the Care Closer to Home specifications by outside doctors in an organisation called the Clinical Senate said:

“…the visionary style of the documents…has compromised our ability to assess if the risks have been addressed.”

The biggest big risk being that lack of clinical workforce and skills will result in a poorer service to patients.

Never mind that merging the NHS with cash-strapped means tested, largely privatised council social care and leisure services threatens the survival of the NHS,

Moving hospital services “Into the community” is a euphemism for a functional merging of NHS community care services with cash-strapped, means tested, largely privatised local authority social care and leisure services, and a wide range of other local authority and central government public services.

It is unclear how the NHS principles of providing a comprehensive health service for everyone who needs it, free at the point of need, is going to survive when merged into this cash-strapped, means tested, largely privatised system. Particularly come 2020, when it is predicted that central government grants to local authorities will be £0.

Large sums of NHS money are already being diverted from the hospitals Trust to the Councils via the so-called Better Care Fund, which is propping up the Councils’ severely depleted adults social care budgets, cut to ribbons by the 40% reduction in central government funding to local authorities since 2010.

On p140 of the PCBC, the Clinical Senate says that the Community Services Specifications omit to say how local authority and secondary care providers have actively shaped this model –

“which depends on social care involvement and funding at the patient level”.

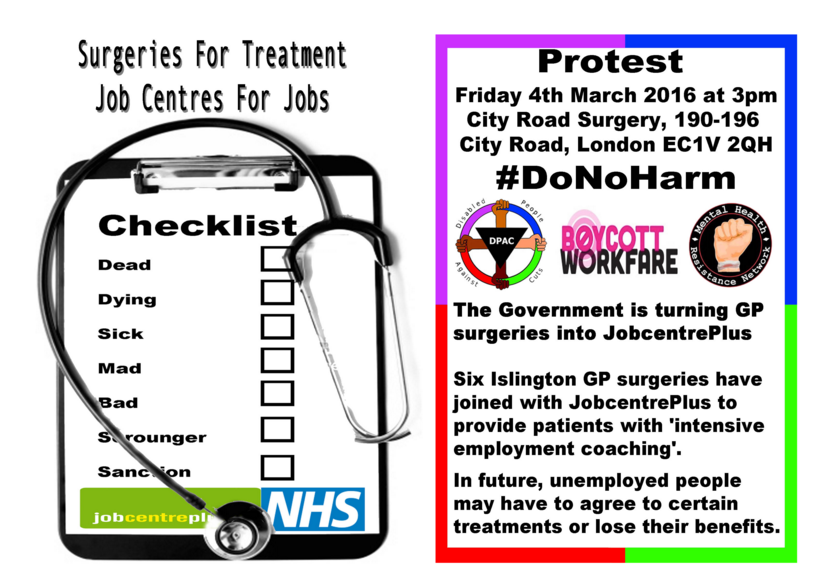

Never mind compromising GPs ethical principles

It is unclear how GPs’ ethical principles will survive when their – hugely expanded – practices, centralised into a few “locality” hubs – also include job centres and GPs are required to provide patients with “intensive employment coaching”.

Couple this with media-inflamed rumblings about whether NHS treatments should be available free at the point of need for patients with conditions like obesity, alcoholism and other addictions, and the threat to doctors’ ethics and core NHS principles is stark.

The context: a deliberately engineered crisis in GP care

Doctors are to Cameron what the miners were to Thatcher.

Right Care Right Time Right Place – and all the other NHS England 5 Year Forward View schemes like it across the country – is where the battle to stop the doctors from going the way of the miners is being fought.

If it were to go ahead, Care Closer to Home looks likely to be the end game in a process of privatising primary care that began under the New Labour government in 2003, when it created a market in primary care by giving Primary Care Trusts powers to negotiate GP contracts with commercial companies.

Marketisation of primary care ended the provision of GP services through a contract with the government, which bound GPs to provide their patients with integrated and comprehensive services and meant they were subject to publicly accountable regulation.

Instead, GP services are now provided under commercial contracts with commissioners – either Clinical Commissioning Groups, NHS England, or both of them jointly, depending on whether the CCGs have taken on full or joint delegation of primary care commissioning.

Calderdale CCG has already taken on primary care commissioning and Greater Huddersfield CCG is due to do so in April 2016 – despite its Chair Dr Steve Ollerton saying in 2014, at a public meeting about the Right Care scheme, that it would be wrong for CCGs to commission GP services, since it would create an obvious conflict of interest.

Under Phase 2 Care Closer to Home, both Calderdale and Greater Huddersfield Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) are going to be commissioning GP and primary care services. They will do this through tendering and awarding unwieldy Lead Provider contracts, to GP federations which are private limited companies set up and run by GPs who are also members of the Clinical Commissioning Group.

They will procure these contracts using the nightmarish “competitive dialogue” process that caused huge problems and delays to Greater Huddersfield CCG’s “procurement” of the Phase 1 Care Closer to Home contract in 2015, leading the hospitals Trust (CHFT) to make a formal complaint to Monitor.

Imagine the chaos that is likely to result when the CCGs are in “competitive dialogue” contract negotiations with their own GP members’ companies.

And then stir in the likelihood, identified by the Clinical Senate, that GPs will offer “resistance and refusal” to Care Closer to Home. (See part 2, Community care commissioning hell – link coming soon.)

Just look what’s happened in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough – where this Lead Provider contracting approach has resulted in the collapse of an £800m contract for care of the elderly only 15 months after its award. Leading to the suspension of the Staffordshire “community” End of Life and Cancer Care contracts procurement process.

Clinical care contracts with commissioners are now the main regulatory control on primary care contractors – despite the findings of the National Audit Office and the public accounts committee that commissioners have insufficient information and knowledge to negotiate such contracts. Which the collapse of the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough contract bears out.

The upshot is that public money is no longer publicly accountable. And deregulatory moves have allowed primary care contractors – now operating under commercial contract laws – to manage new financial risks by adjusting their cost base and restructuring their costs.

This means, for example, that “alternative primary care providers” can impose their own staff terms and conditions and the mix of staff they employ. They can bid for contracts on cut price terms because they’re not bound by national agreements such as:

- terms of employment for salaried GPS

- a requirement to guarantee employees’ NHS pensions

- detailed requirements about how they provide care.

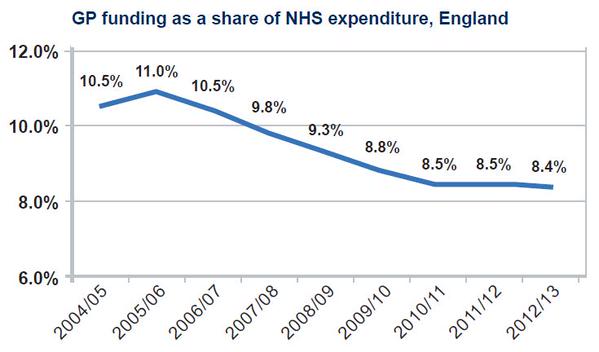

GPs in primary care are at the centre of the NHS. But funding for general practice has fallen in real terms compared to secondary care – even though the government is pressing for treatment to move out of hospital.

The Pre Consultation Business Case makes no mention that I can see of the current GP crisis of underfunding as the context for Care Closer to Home.

Despite the fact that there is a national picture of GP burnout, early retirement, exponential rise in GPs wishing to go to Australia or Canada, and a fall in applications for training places.

The PCBC also omits to mention NHS England’s drive, through the Five Year Forward View, to create a “modern workforce” that is cheaper, less skilled and less qualified and quite probably employed on local terms and conditions – leading to an NHS postcode lottery where wealthy areas can pay more, while poor areas struggle to attract staff.

NHS England’s Five Year Forward View aims to accelerate this process through Vanguard and Care Closer to Home schemes. If Councils’ Scrutiny Committees and the public between them don’t stop these schemes, they will hammer home the final nails in the coffin of publicly accountable, comprehensive GP services that operate on a level playing field for for staff and patients across the country.

After more than 500 GP practices closed – at an accelerating rate – between 2009/10 and 31 August 2014, NHS England – invoking competition law – pushed to open up all new GP contracts to bids from the private sector, and to only use the specific time-limited contract, called Alternative Provider of Medical Services (APMS), that the New Labour government introduced in 2004 to open up primary care to ‘new providers’.

Whose idea is this?

The immediate local organisations that have come up with these Care Closer to Home plans are the 3 NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups in North Kirklees, Kirklees and Calderdale.

But near-identical schemes are being rolled out all over the country; documentation relating to this scheme clearly shows that this comes from central government and its NHS privatising quango NHS England.

The quango’s boss, Simon Stevens, previously worked for the global American private health company United Health as one of its Vice Presidents, and is now aligning the NHS with his previous employer’s systems and methods, the better to enable United Health to bid for lucrative NHS contracts.

Those promoting the so-called Right Care Right Place Right Time scheme (which could more accurately be called Less Care, Fragmented All Over the Place,), claim that this is the brainchild of local clinicians, particularly the GPs on the Governing Body. It isn’t.

Clinical Senate reviews of the hospital cuts clinical model and the Care Closer To Home specifications have made it clear that the Right Care Right Place Right Time plans are based on nationally generated models with no significant local input.

They found no evidence that local clinical staff had been asked about either the hospital model or the model of community care (Care Closer to Home).

Nor could they certify that the proposed models would generate the required quality of care.

The overall plan for merging NHS, local authority social care and leisure services, social services and other public services goes under the rubric of New Public Management – a concept parachuted from on high by Atlanticist politicians who derive their ideas of how to govern from the USA and global management consultancy companies with vested interests in privatisation of public services..

Which patients will be affected?

The main patient groups who will be affected are:

- the frail elderly

- smaller numbers of children and young people

- children with complex needs and their parents

- people with respiratory and cardio vascular illnesses

Roughly how many patients will be affected? The numbers of patients in those categories are not huge, but right now I don’t have figures.

For these relatively small numbers of patients, the whole NHS and social care system is being upended and shaken till it rattles and threatens to fall apart. Why?

See Parts 2 & 3, coming soon.

Brilliant, I had read the business case and was persuaded that there were some good clinical reasons to have 2 centres one for emergency and one for planned care, I also agree on moving care closer to the community-however this article has opened my eyes, well researched and well argued.

Thank you, glad you’ve found it useful.