Going where the wild things are stops Monbiot being bored – a problem for him, given his humdrum life of raising a kid, working and paying the bills – and he wants the rest of us to experience the same thrills. He is an evangelist for rewilding, the modish conservation concept that calls for the reintroduction of top predators like wolves, bear and lynx to certain regions where they have become extinct.

“Wouldn’t it be amazing if everyone had a Serengeti on their doorstep?” he asks at the end of a cute animated video, produced to promote his book Feral.

This is a bit of an unfortunate aspiration, given that the British colonial government threw the Maasai off their land in order to create the Serengeti National Park. The colonialists dumped them in the arid land of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area, where to this day the Maasai say the wildlife gets better treatment than they do. No one is now allowed to live in Serengeti except Park staff and hotel and tourist lodge employees.

Still, Monbiot has resisted the suggestion that rewilding is a form of green grabbing. In reply to my previous blog, on the media hoopla surrounding the publication of Feral, he tweeted that if I read the book I’d find that it dealt with issues I’d raised about green grabbing (and hubris).

So now I’ve read Feral’s Chapter 1, in addition to the chapter published on the Aeon website about rewilding Slovenia. It’ll be a while before I read any more – Calderdale Libraries have one copy of Feral and it’s out with a reader in Halifax at the moment.

Chapter 1 is enough to be going on with – it’s where any writer sets out their stall, to stimulate readers’ expectations about what will follow. So it’s going to be fairly revealing.

Fear and Loathing In Machynlleth

At first glance, the lie of the words on the page shows a surprising lot of I. Still, perhaps Monbiot is emulating the gonzo journalism of Tom Wolfe and Hunter S Thompson, which famously puts the writer’s subjective experiences at the centre of the story.

Could Feral be a kind of Fear and Loathing in Machynlleth? At a guess, without quite as many drugs? I start to read.

Stung by winter sleet, Monbiot is chewing on one of the white grubs he’s uncovered while digging turves in his sodden Welsh garden.

As magical as the madeleine biscuit in Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the grub’s burst of flavour instantly transports Monbiot to his youth, where he awakens to a new day of what reads like disaster tourism in the near-civil war zone of an Amazonian gold rush, but in fact was Monbiot’s investigation of the desperate straits of Brazilian peasants who had been evicted from their land. Forced to scrabble a living in the gold mines, they were thereby destroying the Yanomami people and the forest.

The horror! The horror!

Pausing only to brush his teeth, pick up his notebook and a friend called Paulo, the youthful Monbiot rushes off from the desperado gold miners’ camp on a knight-errant mission to rescue his companion Barbara, who has failed to return from a solitary hike to a Yanomami village in the mountains.

After paragraphs of prose as bald as the moors that Monbiot finds so ecologically dull, he comes upon her in a forest clearing, “radiant as a flower” in the centre of a circle of feather-bedecked Yanomami women who are illuminated by the “stained glass” light filtering through the forest canopy.

Their menfolk having been killed off by the gold miners’ incursions, the women call upon Monbiot to assume the properly masculine role of healer. They need a man to dance the healing dance over a feverish young women. After performing to the best of his abilities, he falls into a faint from which he recovers with a meal of white grubs, tasting just like the ones in his cold, wet, Welsh, boring garden.

Finally, we’ve stumbled across the memory that lit up his dank garden.

For the reader to experience that bewilderingly lovely flight to another reality, to a memory so strong that it obliterates the present, a story needs to cut on the sensation that merges past with present. The action needs to go straight from the sensation, to the exact remembered moment of feeling that sensation.

If that doesn’t happen, the reader doesn’t feel the moment’s weird warp. This failure sets up some distrust of the writer.

Noblesse oblige

Proustian moment dispatched, Monbiot explains its significance for him.

The memory evoked by eating the grub prompts a confession of his envy of the gloriously brutal miners, who carried no burden of civilised restraint and would just as soon shoot someone as recognise their right to exist. While Monbiot, a decent liberal, chafes under the constraint of having to listen to and respect the views and presence of the world’s lower orders.

Previously out of sight and out of mind (like those Maasai who were driven out of the Serengeti), the lower orders, genders and races have gained rights over the last 200 hundred years which, Monbiot feels, have severely curtailed his own freedoms. His address to the reader implicitly assumes that “we” all share his experience.

“As mass communication has enabled those whose rights we formerly disregarded to speak for themselves, to explain the impacts on their lives of the decisions we make, we become increasingly constrained by a necessary regard for others.”

From a class and a gender that, through a long history of organised political struggle, have managed to free ourselves from some of the oppression and exploitation that previously put us beyond the pale, I see the situation a bit differently.

I can’t feel any sympathy with Monbiot’s need to point out what a decent liberal guy he is, who would never dream of retracting or disrespecting the rights that the lower orders now enjoy, despite the boredom he feels at having to accommodate them.

Hair shirts itch

Another reason why Monbiot wants to run with the wild things is to escape the irksomeness and futility of trying to live as a green consumer – changing to low energy lightbulbs, turning down the heating, buying fair trade coffee.

Again using the universalising “we”, but this time only presuming to speak for all environmentalists, Monbiot writes,

“We have urged only that people consume less, travel less, live not blithely but mindfully, don’t tread on the grass. Without offering new freedoms for which to exchange the old ones, we are often seen as ascetics, killjoys and prigs.”

As Monbiot has found, trying to live in a green hair shirt is depressing and miserable. As Monbiot doesn’t seem to have found, it’s also politically pointless and ineffective.

Only some environmentalists advocate green hair shirt consumerism as a solution to the urgent political problems of environmental and social destruction that late capitalism has unleashed.

Like so-called austerity politics, it’s a way of making the public pay for the criminal failings of rich and powerful corporations that dangerously assume they are too big to fail. A political sleight of hand that people are increasingly getting wise to.

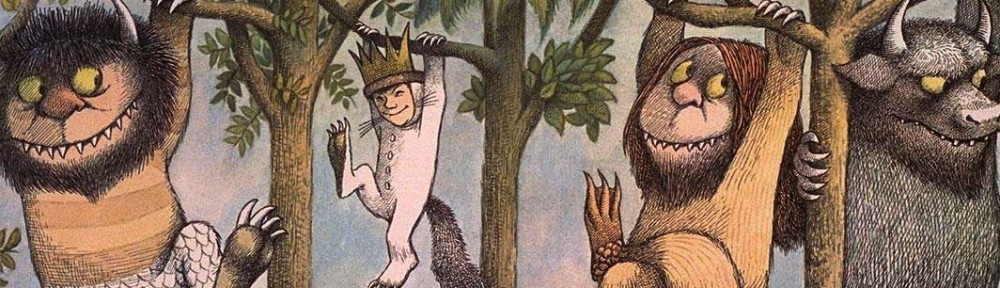

Donning a wolf suit and going where the wild things are is not likely to be any less politically pointless and ineffective – even if, as Max found in Sendak’s Where The Wild Things Are, it’s a great way of dealing with a massive sulk.

To my way of thinking, it makes much better sense to realise that climate change and ecocide are political problems that require collectively fought-for political solutions.

As the No Dash for Gas occupiers have just found out, ending the domination of politics by global oil companies, and stopping them extracting and burning fossil fuels, can generate some major excitement, if that’s what Monbiot’s looking for.

Leave your critical faculties by the wardrobe door

At the end of Chapter 1, Monbiot invites readers to step through the back of his wardrobe, presumably into his version of Narnia. The Narnia stories ask readers to surrender to the charms of a Christian allegory dressed up as children’s fiction. What will Feral ask readers to do? And will it be as oblique about its real intentions as the Narnia stories are?

And why suggest that reading the rest of his book will resemble a trip into the world of childhood fables? Does Monbiot hope that this will induce readers to leave their critical faculties by the wardrobe door?

Mine are bounding like puppies – even tumbling and romping like wolf cubs. Running in circles round me, falling over each other and yelping. They’re not going to be left behind.

They anticipate that, through the back of Monbiot’s wardrobe they will find a below-the-radar advocacy of Payments for Ecosystem Services – something Monbiot has previously denounced as a great greenwashing imposture.

They will shred this like an old slipper.

Rewilding will cost. Where will the money come from? Rewilding Europe is clear that rewilding is a good business opportunity for landowners, exactly because it will make them eligible for payments for ecosystem services.

Although the great landowners have effectively captured the Common Agricultural Policy, it remains, at least in theory, subject to democratic control. If the public would rise off its collective bum, it would be possible to reform the CAP so that it paid for the kind of land use and land management that the public decided was in the best interests of people and planet (in so far as it’s possible to work out what the interests of the planet are).

Payments for ecosystem services will not avoid corporate capture, and these financial instruments will be even less democratically accountable than the CAP. Already, environmental financial instruments like the EU Emissions Trading Scheme have proved to be nothing more than profit-making mechanisms for carbon-polluting companies, criminal scammers and the financial sector. They’ve totally failed to protect the biosphere.

Payments for ecosystem services will rely on a whole raft of yet-to-be-developed financial instruments that are likely to be as dodgy as all the other financial instruments whose crazy and labyrinthine design caused the 2008 financial meltdown, for which the public is still paying.

If, in the land through the back of Monbiot’s wardrobe, it turns out that he’s not advocating payments for ecosystem services as a way of paying for rewilding, it will be interesting to find out how he proposes to fund it.

I shall have to wait for the reader in Halifax to return the book to the library before I can push through the mothballed furs into the wild forest of Chapter 2 – time perhaps to make a wolf suit and hat .

The damage done by farmers to the ecosystem and their lobbying power are discussed again in his latest article on neonicatinoids and bees http://www.theguardian.com/environment/georgemonbiot/2013/aug/05/neonicotinoids-ddt-pesticides-nature