Greenpeace support for the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) has allied it with US national interests and oil companies that stand to benefit from an underwater land grab of around 1.5 million square miles of sea bed. This is the area that UNCLOS has opened up for hydrocarbon and mineral exploration by U.S. firms alone. It includes part of the Arctic sea. At the same time, Greenpeace’s Save the Arctic campaign aims to create a sanctuary in the uninhabited area around the North Pole and a ban on offshore oil drilling and industrial fishing in the wider Arctic region.

There seems to be a massive contradiction between Greenpeace’s simultaneous support for UNCLOS and its campaign to protect the High Arctic from the depredations made possible by UNCLOS. An Arctic sanctuary isn’t going to be much use if the rest of the 32% of the world’s ocean floor covered by the UNCLOS regime is being mined for minerals, gas and oil. Surely it would make far more sense to challenge the whole issue of UNCLOS-permitted undersea land grabs? According to Richard Page, a Greenpeace Oceans campaigner who works on the campaign to Save the Arctic,

“As is often the case with the global legal framework, the situation is not as simple as we might wish. While the race by the Arctic coastal states to claim large areas of the seabed under the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) process is depressing, it would not be helpful to oppose the CLCS process which is at the very heart of the UNCLOS and quite frankly unwinnable.”

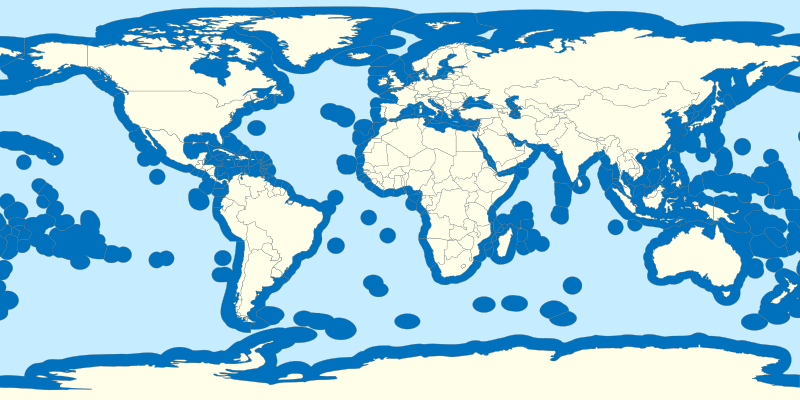

Exclusive Economic Zones claimed by different countries under UNCLOS - created by B1mbo under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Chile license

Greenpeace, ExxonMobil, US Chamber of Commerce, and Hilary Clinton

Together with ExxonMobil, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and the then-Secretary of State Hilary Clinton (among others), in 2011 Greenpeace publicly supported the US ratification of the UNCLOS. Although lack of Senate support meant the US failed to sign up, the US does recognise UNCLOS as customary international law and follows its norms. It would be odd if it didn’t, since the US “led the world in negotiating” UNCLOS, and, through President Reagan’s insistence, also gained a major revision to the seabed mining part of the convention before UNCLOS took effect in 1982.

According to John Norton Moore, Walter L. Brown Professor of Law at the University of Virginia School of Law, UNCLOS provides a strong legal basis for firms to claim the rights to resource exploitation from the sea bed and extends “U.S. resource control into the oceans in an area greater than the land area of the nation.” This has dramatically increased access to many resources, including strategically critical rare-earth elements that are currently only available from China.

46 of the 320 articles of UNCLOS are devoted to the protection of the marine environment, but in the judgement of environmental lawyer Hans Hertell, they don’t amount to a hill of beans. Hertell comments on UNCLOS’s

“failure to enforce basic environmental regulations and to address ecological issues vital to the Arctic at present or in the future.” (p570-1).

And “The Convention’s environmental provisions most relevant to the protection of the Arctic marine environment are” mainly “unhelpful generalities that lack legal teeth and remain largely unenforceable.” (p572)

But Greenpeace’s Save the Arctic campaign invokes UNCLOS, stating that the Convention

“even gives special attention to semi-enclosed seas and ice-covered waters and calls for nations to co-operate to ensure that the environment is protected.”

Greenpeace’s support for UNCLOS’ paltry environmental protection provisions ignores the fact that UNCLOS is a charter for a small handful of rich nations to carry out what is effectively an underwater land grab. It provides the legal framework for oil, gas and other mining companies to make precisely the claims to seabed hydrocarbons and minerals that Greenpeace’s Save the Arctic campaign opposes, with its proposal to create a sanctuary “which would be specifically protected from industrial activities”.

“A colossal resource grab by former colonial powers”

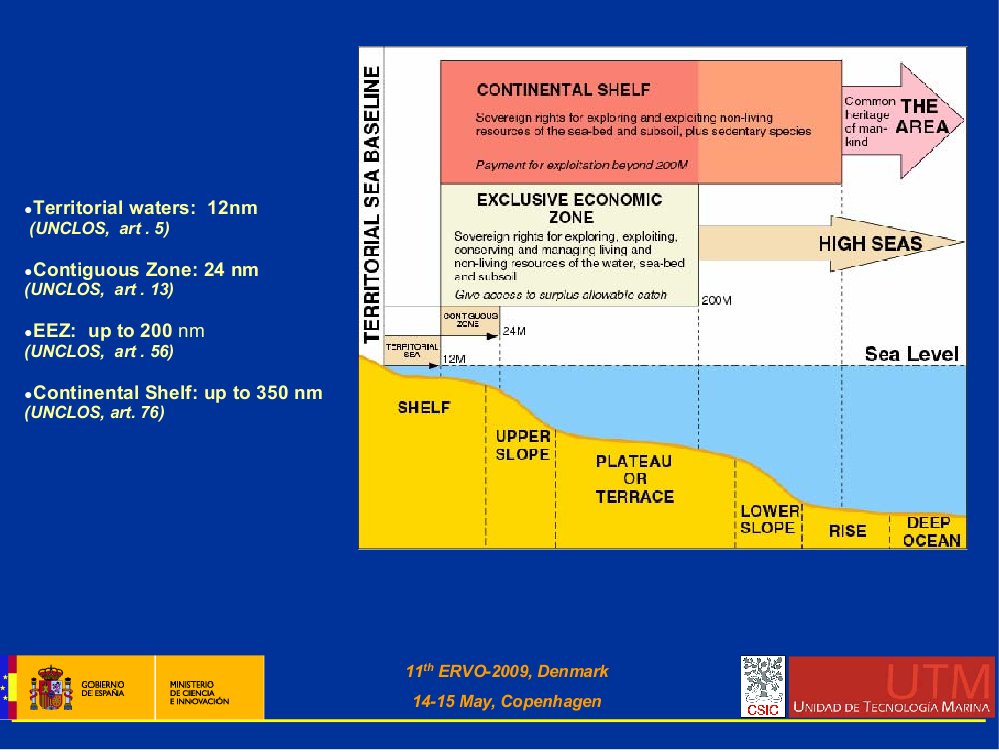

UNCLOS creates Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) over the oceans and the seabeds beneath them, turning them into the property of the maritime states, including uninhabited islands. The EEZs extend for 200 nautical miles off the coast or the island. Countries can extend sovereign rights to the exploration and exploitation of “non living resources” beyond this limit, to take in the adjoining contintental shelf. This creation of property rights over the oceans and seabed is a radical legal change.

Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the sea and its resources were considered a global commons. Before UNCLOS, maritime states had sovereign authority over their territorial waters, which extended 12 nautical miles from their shores. As both supporters and opponents of UNCLOS agree, the motive for the assignment of property rights through Exclusive Economic Zones is the race for fossil fuels and key minerals, including rare earth metals, under the ocean floor.

According to Peter Nolan (Director of the Centre of Development Studies, Chong Hua Professor in Chinese Development and Director of the Chinese Executive Leadership Programme, all at Cambridge University), UNCLOS has facilitated a “colossal resource grab by former colonial powers”. Writing in New Left Review 80, March/April 2013, Nolan points out that many South Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean islands are still subject to administrative control by their former colonial masters.The fact that islands have the same entitlement to EEZs as mainland territories gives the UK, France and the US huge additional EEZs from their colonial island possessions.

Foreign Office Minister Lord Howell with Kaj Leo Holm Johannesen, Prime Minister of the Faroe Islands sign UK & Denmark/the Faroe Islands EEZ Protocol, 25 April 2012.

This was the reason for the Thatcher government war over the Malvinas/Falkland Islands. The largest concentration of UK EEZs covers the oil-rich South Atlantic ocean floor. The EEZ for the Falklands, South Georgia and the Sandwich Islands is 2m square kilometers, which, as Prof Nolan points out, is nearly 3 times more than the UK’s own EEZ. The UK also has substantial EEZs from colonial -era islands that it still controls in the Caribbean and North Atlantic, and the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

France’s EEZs, based on former colonies in the North Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, dwarf the UK’s. The US, despite not having ratified UNCLOS, has still formally recognized the EEZ, claiming 12m square kilometres – the largest territorial acquisition in US history. Most of the US EEZ is from its Pacific Ocean territories – Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, a number of uninhabited islands, Guam, Hawaii, the Mariana Islands and American Samoa.

The three other nations that have benefitted most from UNCLOS are New Zealand, Australia and Russia. All three owe this to colonial appropriation – New Zealand and Australia, obviously; Russia’s maritime status mainly results from its acquisition of Siberia in the 19th Century.

Private property rights and neoliberal environmentalism

A justification for setting up UNCLOS was that the creation of national property rights over marine resources would provide better protection and conservation than the previous system of global commons. Judging from a 2011 US Congressional Research Service (CRS) report that recommended US ratification of UNCLOS, this is just so much greenwash. The CRS Report stated that signing up to the UNCLOS and its marine conservation elements would generate good international pr for the USA, without requiring the US to do anything it wasn’t already doing with respect to living marine resource management, conservation, and exploitation.

UNCLOS’s creation of national property rights over what was previously a global commons is typical of the neoliberal environmentalist agenda. Informed by the 1989 UK publication Blueprint for a Green Economy, neoliberal environmentalism proposed that the best way to protect the environment was by making all environmental resources subject to private property rights and creating market instruments so that these property rights could be traded. In line with the Thatcherite mania for deregulation, no consideration was given to the potentially more effective method of setting required legal standards that would control environmental damage, such as carbon emissions and other forms of pollution.

Blueprint for a Green Economy was based on the work of economist David Pearce, a former adviser to the Thatcher government, who went on to write influential reports for the International Panel on Climate Change. He continued to base his policy recommendations on the neoliberal mantra of private property rights and market instruments. Subjecting environmental resources to private property rights means that all benefits from the resource are the exclusive property of the owner, that the owner can sell their property to other owners and that these rights are legally enforceable.

The failure of neoliberal environmentalism

The adoption of neoliberal environmentalism by the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 created a situation where oil companies and other global corporations effectively captured international, regional and national climate change and environmental policy making (Dieter Helm). The unsurprising result is that these policies have served corporate, not environmental, interests. The failure of these policies is clear from the United Nations Environmental Programme report prepared for the 2012 Rio+20. Carbon emissions, the average global temperature, sea levels and biodiversity losses have gone on rising.

Given neoliberal environmentalism’s obvious failure over the past 20 odd years, why Greenpeace would think UNCLOS is likely to help protect the oceans in general and the Arctic in particular is anyone’s guess. But critics of neoliberalism point out that non governmental organisations are an important part of neoliberalism’s operating method. Greenpeace, running with the arctic hare and hunting with the EEZ hounds, lays itself open to this perception. Particularly since its recent publicity stunt of dropping a flag to the seabed at the North Pole has been seen specifically as a “rebuff” to the Russian flag that was planted on the seabed in the same area in 2007, to support Russia’s claim to the right to any oil or mineral resources between its coasts and the North Pole.

Asked by Changing More Than Lightbulbs to comment, Greenpeace International senior political advisor Ruth Davis said:

“Greenpeace supports the implementation of UNCLOS, including its responsibilities towards the protection of marine ecosystems; and in doing so recognises the legal right of countries with Arctic coastlines to claim an extension of their continental shelves.

“However, having the right to claim an extension does not oblige a country to pursue that claim; nor does it mean that countries are obliged to exercise their rights to drill for oil or undertake other industrial activity in the area claimed.

“At any point, any or all of the Arctic countries could come together with members of the wider international community to propose the creation of a protected global sanctuary in the area of the Central Arctic Ocean. This is a moral and political matter – not a legal one.”

In a story that raises the possibility that Greenpeace may be operating like a useful idiot for Washington and the oil companies, it is a strange twist to find from an article in the Torygraph that Professor Nolan’s chair at Cambridge University is funded by the Chong Hua Foundation, an untraceable organisation whose name apparently means “Respect China”, and that

“Critics of Prof Nolan have questioned whether he would be likely to project Chinese views on what Beijing calls its ‘core interests’ such as Tibet and the Dalai Lama, its territorial claims in the South China Sea or its bid for resources in Africa.”

I wonder? Professor Nolan’s New Left Review article details the West’s and Russia’s stonking underwater land grabs in order to contextualise the relative triviality of China’s current dispute with Japan over a group of uninhabited islands in the South China Sea.

You can read a reply from Richard Page, Greenpeace Oceans campaigner, here.