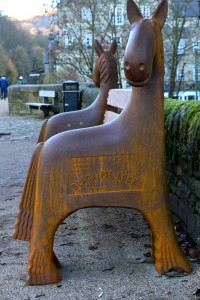

One winter day, I was intrigued to see two cheeky brown pony head sculptures sniffing the air above the wall at the end of the road to Riverside School and the Post Office.

On the tow path the other side of the wall, the two ponies greeted me – bearing the weight of a wooden bench between them. They are enchantingly sturdy, elegant and cheerful. On their flanks, they are branded with the name of the artist – Lucy Casson – and Hargreaves Foundry in Halifax that cast the sculptures.

On the tow path the other side of the wall, the two ponies greeted me – bearing the weight of a wooden bench between them. They are enchantingly sturdy, elegant and cheerful. On their flanks, they are branded with the name of the artist – Lucy Casson – and Hargreaves Foundry in Halifax that cast the sculptures.

Nearly 20 years ago, I’d videotaped Lucy Casson making junk automata out of old Castrol oil cans scavenged from a dump, for an exhibition at the Wolf in the Door Gallery in Penzance. It had been fascinating to watch the process.

Tin Works from Jenny Shepherd on Vimeo.

Now I was curious about how Hargreaves went about translating an artist’s vision into cast iron. I asked Hargreaves Marketing Manager Richard Hall if I could visit and find out how this process worked.

Hargreaves Foundry has a serious track record in casting sculptures – they have cast many of Anthony Gormley’s, including the watchful human figures that gaze out to sea at Crosby and stand disturbingly on the edge of tall buildings in London and Cambridge.

Hargreaves Foundry Manager Andy Knight and Hargeaves Supervisor Pete Lodge talked me through the process.

“Normally the artist will have an idea of what they want to do. We usually ask for sketches and designs and talk things through with them – young artists often have eyes bigger than their bellies – they have grandiose ideas. We often help them find ways to do things cheaper.”

Richard Hall, the marketing manager, added,

“There’s nothing we can’t cast though, it won’t be because we can’t do it, it’ll be about cost. The process varies from artist to artist. Lucy came up and had actually made a wooden model, she had sketches and a budget and gave us some ideas about how to facilitate it. The budget is always the limiter.”

Lucy Casson came to Hargreaves Foundry through Pennine Prospects, which had used Leader Funding for a competition which Lucy won.

About 10-15% of Hargreaves yearly financial turnover is artists’ work, but it depends on any given time. A big artist’s commission can totally occupy the foundry for two months at a time.

Hargreaves’ working with artists started in 1993 with Anthony Gormley. Asked how the working relationship with the sculptor started, Managing Director Michael Hinchliffe said,

“Someone recommended Hargreaves Foundry to him. When Anthony Gormley found us, he was making pieces as big as this room” (The room we’re in is pretty big).

Andy Knight went on,

“There aren’t many foundries left in Halifax – we’re the biggest. There used to be 30 in Halifax. Now there are less than 60 iron foundries left in Great Britain. I remember the days when there used to be around 3,000, up until the 1970s. Basically with the demise of all engineering, the foundries went with it. Our bread and butter was machine tools.”

Andy Knight said that Hargreaves Foundry used to employ 40-50 people in the foundry. Now there are 17 in the foundry, including the pattern shop, and 60 people in all across the company, including the warehouse business.

The big change for the Foundry was the move away from machine tools to rainwater goods – gutters, drainpipes and so on. They import a lot of cast iron water products from China now and this is a mainstay of the warehouse business.

Richard Hall said,

“Hargreaves Foundry is an important player in the cast iron water products business, we supply direct to builders’ merchants.

The irony, or paradox is, if we didn’t have the import business, we wouldn’t still have the foundry. Now the foundry is doing pretty well.”

Michael Hinchliffe, the Managing Director added,

“We’ve got a good order book. We’re more efficient now and we make a wider range of castings. Our standard business is still machine tools – our competitors have all died off. Hargreaves Foundry have survived because we’re better than the others. The few foundries that have survived are working in lots of different industries. There’s cast iron everywhere – a bit like rats!”

Outside, Andy Knight shows me massive crates packed up with machine tools to ship to the States. I’m struck by the global nature of the cast iron business, with Hargreaves importing cast iron water products from China and casting and exporting machine tools to the USA.

Architectural castings like railings, gate posts and lightning columns, are a big part of the Foundry’s business and Hargreaves has been working on the Grid Iron building in Kings Cross, St Pancras. This is a concrete building clad in cast iron columns.

Hargreaves Foundry also supplies Hargreaves Lock Gate company with cast iron, in a relationship which goes back some time.

Micheal Hinchliffe said,

“Just as long as we’re currently adapting and keeping customers and attracting new ones, the future’s rosy.

There’s a fantastic new trend in using cast iron in new buildings, and heritage building refurbishment is a very good market. The Houses of Parliament is tiled with cast iron slates and it has a ten year project of replacing broken tiles.”

Richard Hall said that they were proud that they hadn’t gone the route of cutting wages and racing to the bottom, in an attempt to survive. He said Hargreaves Foundry pays fair wages and although they’re not hiring at the moment, they periodically do take on more staff.

Compared to the past, when people would come in already trained in the essential skills, nowadays the foundry is a niche industry and there are very few people that they can pull in fully trained. Instead, Hargreaves Foundry trains new employees on the job. What they look for are positive, enthusiastic people with some practical skills and the right attitude to work.

A tour of the Foundry, where casting is in process, follows the action as it unfolds. We enter the Foundry as a huge cauldron of white hot molten iron is trundled along an overhead cable, into position over a big mould into which the men pour it when the temperature is right. The process is dramatic, with sparks flying and choking fumes catching the back of everyone’s throats.

We Can Cast Anything from Jenny Shepherd on Vimeo.

We follow the now-empty cauldron back through the cavernous foundry, to watch the process of melting the iron and pouring it into the cauldron. This bit of the process ends with slagging off – an eruption of white hot waste in a shower of sparks like an enormous and furious roman candle.

Then Andy, Richard and Pete take me outside to the start of the process. This is where piles of old iron are stacked ready to be melted down. All the cast iron products made at the Foundry are from recycled material.

It’s a process that could go on indefinitely, as long as there is old iron to be recycled. And in the Foundry, with sand underfoot, sparks flying in the gloom and white hot metal pouring down a chute into a battered cauldron, Richard Hall said,

“This has been going on for hundreds of years. Someone could come back from the 19th century and find it’s still the same process as they were doing.”

It seems fitting that Lucy Casson’s work, which started out around 20 years ago with her re-using junk oil cans, has progressed to a process that re-uses scrap iron.

The Wolf at the Door Gallery in Penzance (now closed), where I came across Lucy’s automata, was run in the 1980s and 90s by Anne Sicher. Anne asked me to make a video of the process of making the automata, to show at Lucy Casson and Andy Hazel’s Tin Works exhibition.

Digitising the video last winter at the WFA studio in Manchester, the technician who helped me commented on how it wouldn’t be possible to make these junk automata in the same way today, since the old Castrol oil cans that Lucy and Andy used don’t exist any longer – oil now comes in plaster containers.

Love this Jenny. My grandad was a moulder in a foundry at blackmires, Holmfield. Steph