Calderdale Council has finalised its Calderdale Energy Future (CEF) Covenant, that members of the new CEF Panel will have to sign. Here it is:

Calderdale Energy Future Covenant

We the undersigned are committed to working together to create Calderdale Energy Future

We will collaborate to build a low carbon Borough which benefits our communities, businesses and landscapes.

We will work to ensure that Calderdale takes a leading role to reduce carbon emissions and to build a resilient low carbon economy.

In particular we commit ourselves to:

- Reducing the carbon emissions of our own estate and operations by 40% by 2020 leading to an 80% reduction by 2050 from a 2005 baseline

- Creating a low carbon economy which involves everyone, preserves and enhances Calderdale’s natural landscapes and contributes to improving the health and wellbeing of local people

- Supporting a programme of best practice sharing

- Reporting each year, to the Energy Panel, on the progress we are making

We commend the communities, organisations and businesses in Calderdale who are reducing their carbon footprint and helping to tackle climate change

We now call on all communities, organisations and businesses in Calderdale to sign the Energy Future Covenant and help to deliver Calderdale’s Energy Future

Company / Organisation / Individual Name________________________________________________

Signed _________________________________________

Date_____________________

Job Title / Position ________________________________

Problems with asking signatories to meet the Calderdale Energy Future carbon reduction target

I’ve been thinking that there are problems with asking signatories to meet the CEF carbon reduction target of 40% reduction on 2005 levels by 2020. One problem is that it’s not clear that this is workable. The other is that it doesn’t seem socially just.

Is it workable for signatories to commit to reducing their carbon emissions in line with the CEF target?

Requiring signatories to agree to reduce their carbon emissions in line with the CEF target doesn’t seem very workable. For a start, how many people/organisations know what their carbon footprint was in 2005? Probably very few. So how can they show that they’re reducing them from that level, in line with the CEF target? But Simon Tao, Energy Help wind farm developer and community virtual green power generator, says this may not be such a problem.

“If organisations want to reduce their carbon footprint, they need to have a baseline to work from. But they can still monitor their immediate carbon reductions now and offer this info, so others tasked in this area can do the analysis globally from 2005 levels.”

Then there’s the question of what definition of carbon emissions the CEF Covenant wants people to use. Their production emissions? Or consumption emissions? They’re very different. The consensus seems to be that consumption emissions give a much truer and more useful picture – partly because they take responsibility for carbon emissions produced in countries that export the goods and services which we import & use; partly because this allows the rebound/backfire effect of increased energy efficiency to be identified & taken into account.

And is there a standard carbon footprinting tool that Calderdale Council wants people to use? Different carbon footprint measuring tools will give different results.

Complying with the target will mean reducing carbon emissions by about 3%/year, every year. How feasible is this? How will this be audited/reported? What will happen if CEF Covenant signatories fail to reduce their carbon emissions by the targetted amount? Given the Climate Change Committee’s recent evidence, that last year the UK as a whole reduced carbon emissions by 0.8% (when you take away the reductions due to mild winter and economic recession), how will CEF signatories buck this trend?

A “one size fits all” target is inequitable

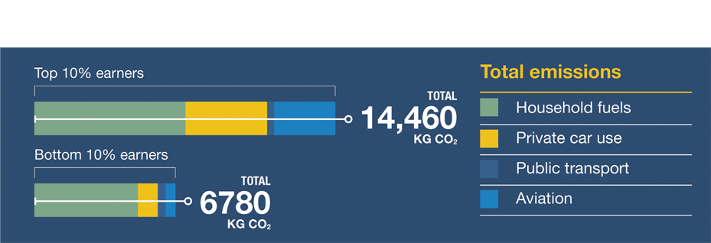

There’s a strong argument that a ‘one size fits all’ target is socially inequitable. Research from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation Climate change and social justice programme shows that carbon emissions are directly related to income – ie higher income households emit far more carbon emissions than lower income households. Asking both high and low income households to reduce emissions by the same amount seems quite inequitable.

Lower income households might not be able to reduce their emissions by 3% for various reasons – including the fact that they can’t cut their energy use and general expenditure, with all its embedded carbon emissions, any further. Various presentations at the 2006 Inequality and Sustainable Consumption Seminar at University of East Anglia made the point that social fairness requires low income/poor households to have more access to transport, housing and other socially necessary products and services that produce or embed carbon emissions – not less.

So it’s socially unjust to ask for a 3%/year carbon reduction, year on year until 2020, from people who may already be vulnerable and socially excluded by virtue of their poverty and inability to access transport, more heating and other necessities.

We need climate justice at a local scale

“Social justice and low carbon communities” by Sara Fuller and Harriet Bulkeley, Durham University, May 2012 reviews the justice aspects of current policies/programmes aimed at supporting low carbon communities in the UK. It says that it’s unclear how community-based approaches to making a socially just transition to a low carbon society can achieve this goal. To make a socially-just transition requires attention to climate justice at a local scale. This involves:

- Distributive and procedural aspects of climate justice.

- Responsibilities, duties and recognition of structural conditions that affect people’s access to climate justice

Distributive aspects of climate justice involve:

- deciding who has the duty to reduce their carbon emissions

- deciding how the costs & benefits of reducing carbon emissions will be shared

- recognising structural conditions that create vulnerability and make it unreasonable to ask for carbon emissions reductions

Procedural aspects of climate justice involve:

- working out what responsibilities people and organisations have for taking part in climate decision making

- what rights people have to take part in climate decision making

- recognising structural conditions that mean some people/organisations are included in climate decision making and others excluded.

These arguments can also extend to businesses – some are far more carbon-emitting than others, and some need to grow in order to provide green jobs and skills for local people. It’s not really appropriate to apply a one size fits all carbon reduction target to them either.

So I think Calderdale Energy Future and its Covenant need to explicitly aim for distributive & procedural climate justice.

Better ways of showing a commitment to reducing carbon emissions

There could be better ways for people/organisations/businesses to show their commitment to reducing carbon emissions. Like:

- Self-defined pledges to reduce carbon emissions in whatever way people choose.

How about a paragraph in the Covenant that replaces the commitment to reduce carbon emissions in line with the Calderdale Energy Future (CEF) target, with people’s own pledges to reduce carbon emissions? It could read something like:

In 201………..(insert year), I/we pledge to:

- take the following actions to reduce carbon emissions……………………………………… (insert 1-3 pledges)

- display this pledge in ………………(insert place of display)

- report on the success (or not) of our pledged actions at the end of the year

A reporting process would be necessary and this could be attached to an annual awards party. People could also make a brief online quarterly report in a CEF signatories’ online group or CEF Covenant Facebook page. This could help people keep on track with their pledges, and see how others are doing.

Signatories could make their pledges at a pledge ceremony. It could be a bit of a party, a photo opp for local media and raise awareness of the CEF Covenant.

There could be a list of suggested pledges, for people who might not be clear about what they could do.

Reasons for self-defined pledges

- I know from experience that pledges work. Last year I signed an online pledge not to fly in 2011. I stuck the pledge on my kitchen noticeboard where everyone could see it and ask what it was about. A couple of times I wanted to take a flight but didn’t because of the pledge, and because friends & family knew I’d made it. Community based social marketing also shows that public pledges are effective ways for people to commit to taking action.

- Letting the signatory choose for themselves what they’re going to do to reduce carbon emissions increases the level of engagement, because people make a positive, self-directed decision about what they’re going to do, instead of just ticking a box for an abstract target that’s handed to them.

- This also avoids social injustice problems somewhat, because people can decide for themselves what they can afford to do. For example, people could decide to send their children to school on a walking bus, or to fundraise to insulate their community centre, or do something with Incredible Edible or other community food growing schemes. People could decide to campaign for better public transport, by writing to the local paper, posting on Facebook, and/or by talking to their Councillors/MP. All these things would reduce carbon emissions. None of them would require a cut in consumption, or spending money to increase energy efficiency or install renewables, which people on a low income or struggling small businesses might not be able to do. But they can still take action to reduce carbon emissions, and this should be recognised as equally valuable.

Simon Tao agrees that,

“In terms of recognition of achieving targets, there will be pressure points where reducing emissions could be monitored. For example if “better” public transport was made available and Highways noted from statistics they collect that the number of vehicles consistently was reduced on a particular route, then this could be translated into carbon reduction, but it’s not easy to quantify. If fewer vehicles were on the road, would all the fuel consumption in an area via the petrol stations start to decrease? Would the refinery stations show a decrease nationally if a government policy was applied nationally?”

Invited to comment on these ideas, Calderdale Council’s Environmental Officer Emma Appleton said,

“Following your suggestions, the Council will be expanding the covenant to include a more flexible approach which can be tailored to suit the needs of the individual or organisations but still support Calderdale Energy Future in achieving its ambitious targets and framework.”