For information on how individual households can reduce carbon emissions, please check out insulation and switching to a renewable energy supplier.

If you’re looking for ideas for how to reduce your energy use at home, you might be interested in these open house events where you can look round retrofitted houses. There are some in and around Manchester and Salford.

The best laid plans of mice and men…

Despite twenty years of insulation, draught proofing, better energy efficiency in fridges, washing machines, light bulbs and so on, provisional 2010 statistics from the Department for Energy and Climate Change show that 2010 residential carbon emissions were eight percent higher than they were twenty years ago, in 1990.

It has been pointed out that if we want to reduce energy use, talking about and aiming for increased energy efficiency is probably not the right way of approaching the problem. Increased energy efficiency doesn’t necessarily lead to reduced energy use. Instead, we should probably be talking about and aiming for energy conservation – a term which has fallen out of favour.

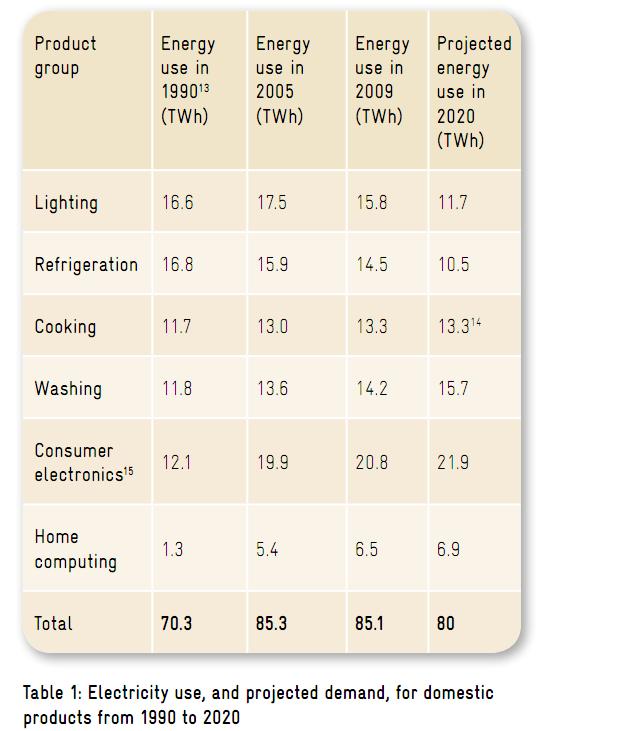

The main reason why residential carbon emissions have gone on rising is that we use more energy now in our homes and other buildings. Appliances like fridges and tvs have got bigger. So even if they’re more energy efficient, they guzzle more energy and produce more carbon emissions. And we own more computers and consumer electronics than we did in 1990, and spend far more time on them too. Domestic electricity use is projected to stay well above 1990 levels at least until 2020. (Source of the table, Energy Saving Trust, The Elephant in the Living Room, p17.)

However, household electricity use has gone down since 2008, according to recent information from the Office of National Statistics. This may just have something to do with the fact that electricity costs have rocketed while the economy is shrinking and unemployment is rising.

Home energy carbon emissions are all our fault – or are they?

The government (and some righteous greens too) like to suggest that the problem is us, the public. We simply don’t know how to behave appropriately, in the way we use energy to run our homes (and other buildings). For example, in its 2008-2009 Report on programmes to reduce household energy consumption, the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee sighed, “The hardest task will be to change behaviour through helping people understand what they need to do and helping them to do it.”

Personally, I find this patronising and unhelpful. It ignores research that shows that most people already want to live more sustainably, and that we meet real barriers and obstacles in trying to do this – such as:

- cost – insulation’s expensive, most people can’t afford it, and the Coalition government has just whipped out all the home energy insulation grants from under people’s feet, in order to make us pay for home energy retrofits through the Green Deal

- hassle – for example, in houses that can’t be insulated through simple cavity wall and loft insulation, there is a major hassle factor in clearing out rooms and attics in order to insulate interior walls

- lack of clear information about appliances’ energy efficiency – for example, when I was looking for a new washing machine, I wanted to buy the most energy efficient one, but couldn’t find a single one with the Energy Saving Trust recommended energy efficiency label; and I only just found out (through researching info for this webpage) that an A rating is no longer particularly good – the most energy efficient washing machines are now A++

So, instead of moaning about the public’s hopeless behaviour, maybe the politicians should also get on with the job of legislating to decarbonise the energy industry, effectively regulating the main players in the energy efficiency market and supporting the Energy Bill Revolution campaign.

If you do want to reduce carbon emissions from your home ( or other building)…

Switching to a renewable energy supplier is probably the single most effective way of reducing carbon emissions from your home or other building.

Although there are obviously things that individual households can do to reduce energy use, retrofitting houses to make them energy efficient is expensive and most households can’t afford it. This is why EnergyRoyd supports the Energy Bill Revolution campaign. Forget the Green Deal.

The paradox of rebound and backfire

Increasing home energy efficiency doesn’t always reduce carbon emissions from home energy use. This is because of the problem of rebound or backfire.

When a household makes their house more energy efficient, they don’t just save energy, they also save money (assuming energy prices aren’t rising at such a rate that they cancel out the savings made from using less energy).

If people have more money, they will either save it or spend it. Either way, unless they save it in green savings schemes or spend it on carbon neutral goods or services, this extra money will cause more greenhouse gases to be emitted. This is called the rebound effect.

Often when people improve the energy efficiency of their house, they end up using some of the savings on their energy bills to pay for additional energy, in order to increase their level of comfort. Studies show that this rebound effect is usually around 30%.

If household spending out of the savings from their increased energy efficiency more than cancels out the carbon emissions reductions, this is called the backfire effect – an extreme form of rebound.

Better regulation and legislation would help

The Buildings section of this website reports on ideas for reducing domestic carbon emissions by:

- legislation and regulation of the energy companies

- green building standards for the construction industry, property management businesses and new public buildings like schools and hospitals

The Energy Saving Trust (EST) says that people who want to take action to reduce their residential carbon emissions face a “regulatory jungle”. So we need clearer, more effective regulation of the main players in the domestic energy efficiency market:

- local authorities

- housing associations

- builders

- energy companies

- appliance manufacturers and retailers

- (leaving out the banks for the moment)

How about:

- introducing mandatory energy efficiency requirements for appliance manufacturers and mandatory energy efficiency labelling for retailers (replacing the voluntary EST “recommended” energy efficiency label)

- reinstating public funding for domestic energy efficiency programmes that the coalition government cut in the April 2011 Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR). The evidence is that far more people insulate their houses when this is funded by grants and carried out by local authorities on a street by street basis. So the CSR cut of 80 per cent of the Leeds City Region local authorities’ funding for domestic energy efficiency programmes probably wasn’t such a great way to go about reducing carbon emissions from residential energy use. The Climate Change Committee which advises the government about how to reduce carbon emissions has recommended that the six big energy companies should have to pay for all the home insulation and energy efficiency improvements needed to meet the 2022 targets for reducing household carbon emissions.

- this would make it possible to abolish the Green Deal, as the Climate Change Committee recommends, given its many weaknesses. These include the fact that households in fuel poverty will be unable to access loans for domestic energy efficiency measures, because their low energy consumption makes it unlikely that they will be able to satisfy the Green Deal “golden rule”, which is that loans are only available to households whose energy savings will cover the cost of repaying the loan.

- making subsidies available for insulation and related repairs during house renovation and re-roofing, and at the same time strengthening Building Regulations about minimum energy efficiency requirements when renovating and re-roofing houses

- requiring energy companies to increase renewable energy generation, and to stop incentivising high energy use through their perverse pricing policy, which reduces the cost per unit of energy as more is consumed. Instead, wouldn’t it make more sense to set low unit prices for low levels of consumption, and raise the cost per unit as more is consumed?

Just some suggestions. Anyone else got any ideas? Please use the comment box or email them in through the contact form.

Updated 27 Jan 2013