The Green Deal is yet another Coalition government proposal for a public private partnership. It effectively outsources local authorities’ home energy efficiency programmes to the private sector. Leeds City Region (LCR), which includes Calderdale Council, is currently preparing a business plan for LCR authorities to set up a public private partnership with a commercial Green Deal provider.

The Green Deal, a market-based scheme for energy- and carbon-saving retrofits to homes and business buildings, aims to replace local authorities’ publicly-funded programmes for home energy efficiency improvements. LCR funding for these programmes was cut from £20m/year to £4m/year by the April 2011 Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR). The funding ends completely in 2012.

We have until October 11th to make views known to councillors

The LCR Leaders’ Board will make a decision on the LCR Green Deal business plan at their October 11th meeting. A Leeds City Council officer who is working on the business plan says,

“Until then, I am unable to provide any further details.”

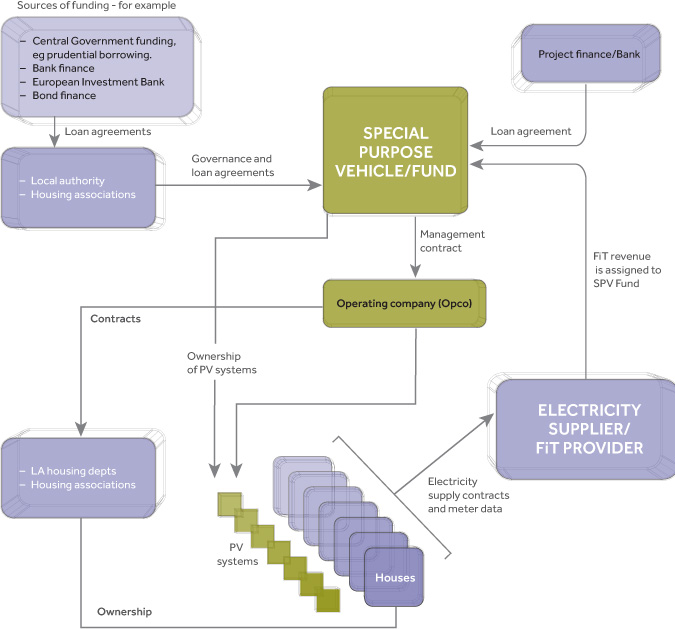

Surely there should be proper public consultation in Leeds City Region about a Green Deal public-private partnership? The local authorities’ Green Deal finance model is based on the creation of a “special purpose vehicle” – a type of assets-holding entity made famous by Enron, the American energy company which collapsed in scandal following revelation of its false accounting practices.

A special purpose vehicle, aka a “bankruptcy remote entity” and a “derivatives product company”, has to repay its debts even if the scheme or parent organisation it holds assets for goes bankrupt. And this at a time when the Coalition government is cutting public spending to the bone because a large amount of our taxes have gone to create a welfare state for bankers, and it doesn’t want to create more public debt!

The Green Deal invites householders and businesses to contract with accredited Green Deal Providers to install up to £6,500 worth of energy efficiency measures and renewables, taking out a loan which they repay (with interest) through their energy bill, on a “pay as you save” basis. The Coalition Government sees local authorities as key to marketing and financing the Green Deal.

Green Deal interest rates must be low enough for the customer to be able to repay the loan over 25 years, out of the savings on their energy bill. Local authorities can borrow at lower rates than the commercial sector, and this is a big reason why the Coalition Government is keen for local authorities to enter partnerships with commercial Green Deal providers.

We don’t need another public private partnership

We don’t need another public private partnership – the record on outsourced public services is dismal, with levels of complexity and secrecy that constitute moral hazard and cost the public dear. They are also very bad value for money: for example, the capital cost of rebuilding Calderdale Royal Hospital in Halifax was £64.6m, but the Private Finance Initiative scheme will end up costing Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust a total of £773.2m.

A Report on the £10bn sale of shares in Public Private Partnership companies found that,

“Government monitoring of the sale of equity in PPP companies is inadequate, infrequent andunder-estimates the scale of transactions. Meanwhile banks and construction companies are ratcheting up large profits extracted from what is ultimately publicly financed investment.”

The Report found that the Treasury PPP database had no information about secondary sales of equity (selling on shares to other buyers) in Calderdale Royal Hospital, but when the Report’s author, Mr Whitfield, went through company accounts and other documents, he found shares in the hospital had changed hands nine times since 2002.

The BBC asked five of the companies which had sold equity in Calderdale Royal to disclose the profit they had made from the deals, but was told the information was commercially confidential.

The Report found that average profits on sales of equity in PPP companies was 50.6%. These massive profits must be at least part of the reason for the rocketing costs of the Calderdale Royal Hospital PFI.

Need to improve home energy efficiency

We do need to improve the energy efficiency of the UK’s notoriously leaky homes and workplace buildings. In 2011, an estimated 6.4m UK households were living in fuel poverty.

And carbon emissions from burning fossil fuels in order to heat, light and power our homes and other buildings are extremely high.

“A quarter of the UK’s carbon emissions comes from the energy we use to heat our homes, and a similar amount comes from our businesses, industry and workplaces.”

(Department of Energy & Climate Change)

But a public private partnership is not a good way of paying for the infrastructure costs of reducing energy use in our homes and workplace buildings. More ethical, efficient and accountable sources of finance include:

- the Energy Bill Revolution, which proposes a national retrofit programme funded by carbon taxes

- green mortgages which would pay for home owners to retrofit their houses to save energy

- grants and other support for businesses investing in renewable energy generation

- green quantitative easing by the Bank of England to provide the government with money to invest in energy saving retrofits and renewables

Democratic accountability – or lack of it

Camden Council in North London has carried out an online survey asking people in the borough what they think of the Green Deal:

“Your opinions will help us to decide whether this scheme would work in Camden and if the Council should lead on delivery of the Green Deal in the borough.”

The survey asked:

“ What role would you like Camden to play in the Green Deal?”

and gave three options to choose from:

- “Camden should take on financial risk and become a Green Deal provider

- Camden should offer advice to residents on Green Deal and help support local delivery from the private sector

- Camden should ignore Green Deal and leave it to private sector to deliver”

Without any public consultation that I’m aware of, Leeds City Region’s Chief Executives have recommended that Leeds City Region Leaders’ Board prepare a business plan for LCR local authorities to enter into partnership with a commercial Green Deal provider. LCR Leaders’ Board have accepted this recommendation and will consider the business plan at their October 11th meeting.

Councillor Janet Battye was representing Calderdale Council on the LCR Leaders’ Board when it approved the preparation of the Green Deal business plan. I invited Councillor Battye, Councillor Tim Swift (Leader of Calderdale Council) and Councillor David Hardy (Chair of the Calderdale Council’s Economy and Environment Scrutiny Committee) to explain Calderdale Council’s role in the Green Deal and to comment on this article. Councillor Tim Swift has just replied:

“Thank you for this. I have been away and only just able to read this, so should add if no one has done already that I’ve now replaced Cllr Battye on the LCR Leaders Board. I need to look into e [sic] points you raise in more detail.”

I look forward to including Councillor Swift’s comments asap.

LCR’s proposed public-private partnership approach to the Green Deal is based on the Domestic Energy Efficiency Pilot that ran last year in a number of LCR authorities, including Calderdale. This approach sees LCR local authorities as

“working with one or more delivery partners, levering in private sector investment and management resources” while having “a central role in the initial contacts with customers and…a strong input to prioritising areas and demographics…” so that “ the city region/local authorities would be influencers and enablers, establishing the framework for delivery by partners and monitoring and overseeing its implementation.”

It’s not clear how well the pilot public-private partnership worked in Calderdale – when the Department of Energy & Climate Change evaluated the pilots, Calderdale Council hadn’t procured a private sector partner for its part of the Domestic Energy Efficiency Pilot. I’ve asked Calderdale Council and Leeds City Council for an update, but haven’t received any information.

The financial sector & the Green Deal

Leeds City Region states that

“Financing the Green Deal is a significant issue… It is clear that private sector are currently cautious about performing this financing role. Government is therefore looking to local authorities to consider playing a central role in this respect, particularly in the early years. This could [be] funded for example, through prudential borrowing… Birmingham Council is currently implementing a prudential borrowing scheme to support Green Deal delivery in their area.”

Leeds City Council has previous form in overloading itself with debt incurred through private finance initiatives (PFI) – it’s currently carrying £2.2bn PFI debt and this is set to rise when it signs off two more PFI contracts in the coming months. One of them – a PFI project to build 388 new homes and refurbish over 1,200 in Little London, Beeston Hill and Holbeck – is in trouble since one of the banks funding the project has pulled out. You’d think this might give LCC pause for thought about the wisdom of taking on more debt to finance the Green Deal.

The Department of Energy & Climate Change (DECC) reckons that the capital costs of the Green Deal could be £8.25 billion by 2020, while Transform UK estimates that investments of £111bn are needed by 2020 in order to improve the energy efficiency of UK households.

The money has to come from somewhere, and the Green Deal looks like a bonanza opportunity for the financial sector. Take this statement from DECC’s Green Deal Finance Note about the role of the financial industry within the Green Deal:

“Companies seeking to become Green Deal providers are currently considering the best approach to financing their activity. It is possible that some Green Deal providers will choose to use retained earnings, or on balance sheet capital markets debt. Equally, companies may also wish to utilise bank debt.

However, we know that balance sheet treatment will be a serious consideration for any company seeking to secure a significant market share and generate large volumes of sales. Potential Green Deal providers are therefore likely to be interested in an alternative off-balance sheet approaches to financing Green Deal provision. Depending on the structuring of any special purpose financing vehicle, opportunities may emerge for investment in equity, and to supply subordinated debt and senior debt. It is envisaged that any Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) entity seeking to refinance via the capital markets would also issue a range of bonds at different tenures, providing investors with opportunities to acquire Green Deal securities.”

What does this mean? From looking up all the financial jargon, I’ve discovered that it basically means, here’s an opportunity for the banksters to:

- Lend Green Deal Providers long term, interest-bearing loans, that the borrowers either record on their balance sheet, or hide (off balance sheet) so the loans don’t appear on their balance sheet – making them look better off than they are, and allowing them to get round “negative debt covenants” – ie restrictions on the amount they can borrow.

- Get into the kind of dodgy dealings that have already caused such global turmoil and led to recession and the creation of welfare states for bankers – for example: lending money to special purpose vehicles (aka “derivatives products companies”) which exist in order to borrow money which the lender will be able to recover even if the borrower goes bankrupt, and which the lender can also use as a kind of collateral for swaps and other credit derivatives instruments. (Swaps are when finance companies exchange one debt or security for another. They are one kind of credit derivatives instrument. Others include basically turning debts into assets and selling them to other investors, or transferring the credit risk to another party while keeping the loan on your own books.)

- Put local authorities in the position of assuming “junior” or “subordinated” debt. Marksman Consulting shows a local authority’s “subordinated” debt could be around £75m for the first stage of the Green Deal, when it provides all the finance to get the scheme off the ground and retrofits 15,000 homes. It predicts that a local authority’s junior/subordinated debt would increase for further phases, when private sector finance comes in and the number of retrofits rises.

(Update 30 September 2012:

“The LCR is now working on a business case (supported by Marksman) to justify c £75m of prudential borrowing from LCR authorities in order to kick start the Green Deal locally. Leeds is acting as the anchor authority so colleagues from housing, legal, finance, procurement, regeneration etc are being involved in the decision process. It is planned to take a report to LCR Leaders in October and to complete procurement by end of 2013. In the interim, Leeds is working on a Green Deal Go Early project to attract ECO funding to some of the most deprived parts of the city.”

Leeds Climate Change Partnership Draft Minutes of the meeting held on 02 July 2012 [PDF] )

Green Deal public-private finance model

A group of finance companies, plus the Energy Saving Trust, is developing a Green Deal financing and delivery model for local authorities. The group consists of:

This group is called Local Energy Efficiency Project.

Birmingham City Council and a group of North East Councils led by Newcastle City Council have already adopted its model, described by Marksman Consulting as “a Public Private Partnership model”. This is almost certainly the model that the LCR Green Deal business plan is working with.

Worldwide Commodities reports a partner at Marksman Consulting as explaining that,

“Under the model we are proposing they [local authorities] could set up a not-for-profit company that would borrow the necessary capital and then appoint a service provider, such as an energy company or building firm, to do the work.”

I can’t quite figure out the details and need to fact check – but the not for profit company, presumably, is the operating company shown in this graphic as some kind of subsidiary to the special purpose vehicle that DECC’s Green Deal Finance Note refers to. (Graphic by the Institute for Sustainability.)

Worldwide Commodities also quotes Sean Kidney of the Climate Bonds Initiative as explaining that large-scale local authority-led Green Deal initiatives will also allow councils to bundle up the resulting debt and access the bond market in order to achieve more favourable interest rates:

“… this approach could deliver a large enough market to give the bond market the liquidity it needs.”

Green Deal and rebound risks

Risks attach to all public private partnership arrangements. As their history shows, by outsourcing public services to private firms, the quality of the services declines, while private profits and the cost to the public soar.

There are specific risks with the Green Deal. They include the complex problem of rebound – the situation when increased energy efficiency leads to increased energy use. This can happen directly, as when the reduction in energy bills encourages householders to use the savings on increased comfort, using more heat light and power; or indirectly, when householders spend their energy bill savings on other items, which increase their carbon footprint.

The Local Energy Efficiency Project (LEEP) reports that,

“ the credit risk linked to realising sustained emission reductions and energy savings directly impacts its implementation. Investors need to be reassured of the long-term performance and sustainability of the scheme when its success is dependent on the energy use behaviour of householders and hence the continued support of policy-makers.”

If the rebound effect means that Green Deal customers end up not saving enough energy to repay their loans out of pay-as-you-save on their energy bills, investors won’t get their money back, so they won’t invest.

LEEP says that local authorities have limited capacity “to manage economy-wide rebound effects.” And that reducing “indirect rebound effects may be better locked-in through complementary policies at the national level.”

It’s not clear that there are any national policies to do this. Apart from a general government desire to “nudge” households and businesses into changing their behaviour.

So the financial risks of the Green Deal are probably higher than for most public private partnerships.

Cui bono? Who benefits?

The Green Deal is part of the Coalition Government’s ideological agenda of cutting public spending and outsourcing public services to the private sector. They call this the Open Public Services agenda.

In line with this agenda, the Green Deal aims to provide opportunities for the financial sector to profit from lending money to the public sector to carry out activities that we formerly paid for out of taxation- before all our taxes went to bail out the financial sector.

Private finance initiatives in the NHS and education have turned out to be very bad deals for the public, wringing out large profits for the private sector and costing the public sector dear. Started by the Tories and continued under the New Labour government in order to avoid debts appearing on government balance sheets, private finance initiatives (PFIs) have proved to be a form of “off balance sheet capital debt” that has cost us, the public, far more than if the government had borrowed the money themselves on the balance sheet in the first place. Instead, governments hid the debt by letting the private sector pay for building schools and hospitals, and then lease them back to government at rates that cost an arm and a leg.

The Green Deal public private partnership isn’t likely to be any different from more or less disastrous previous public private partnerships/ PFIs in:

And so on.

Speaking back in 2009, Vince Cable said:

“PFI has now largely broken down and we are in the ludicrous situation where the government is having to provide the funds for the private finance initiative.”

and

“The whole thing has become terrible [sic] opaque and dishonest and it’s a way of hiding obligations.”